The psychological resilience movement promised to emancipate us from suffering and empower us to overcome whatever adversities life threw our way. However, increasingly it’s seen as a tool that enables worker exploitation. How did it come to this?

As we will see, the seeds of the movement’s decline were sown long ago. Fortunately for all of us, a new generation of thinkers is building models of resilience that deliver on the initial promise as well as being fit for the complexities of 21st century business.

What’s the Matter with Resilience in the Workplace?

The workforce resilience industry has boomed over the last two decades. Nowadays, it’s a staple of workplace wellbeing strategies. And why not? Who wouldn’t want to empower employees with the skills and know-how to handle stress and overcome adversity?

However, despite its popularity, the evidence of its real-world efficacy has been patchy. Moreover, a growing chorus of notable discontents argues resilience training is a distraction from systemic issues and enables victim blaming, consequently doing more harm than good.

Here at Allos Australia , we have shared this scepticism for quite a while; however, loyal readers will know that we also don’t fall for such simple binaries. The truth is always more nuanced. Plus, there’s always the risk of throwing the baby out with the bathwater when theory doesn’t translate perfectly into practice. A more measured approach would be to step back, look at the bigger picture, and see how we might build and broaden. Or, as Carl Jung put it, “We don’t so much solve our problems as we outgrow them. We add capacities and experiences that eventually make us bigger than the problems.”

So, right now, after years of pandemic doldrums and all the cumulative stress and uncertainty of economic, energy, and climate crises at our doorstep, it’s time for workplace resilience to grow up and step up to the challenges at hand. Here’s how we believe that can happen.

Where did Workplace Resilience come from anyway?

The concept of resilience can be traced back to 17th-century material sciences. Later, the Navy popularised its usage in describing how well ships could withstand a barrage of cannon balls. Following that, the concept crept into basically every other scientific discipline you care to think of – psychology being one of the most recent.

However, withstanding and bouncing back from the assaults of life have a far more ancient history. In fact, surviving and thriving, despite the odds, is something humans have been doing since the year dot. One could argue that the world’s spiritual traditions are essentially eons of condensed wisdom on doing just that.

To be fair, there are many accomplished and sophisticated operators in the resilience space doing great work, but outside those pockets of brilliance the quality becomes questionable. A lot of the advice on resilience bandied around workplaces today has the fingerprints of the ancient Greek and Roman Stoics all over it. Perhaps it’s unsurprising then that Stoicism is experiencing a revival in pop culture with books and podcasts with titles such as “The Daily Stoic” and “How to Think Like a Roman Emperor”.

However, while Stoicism is a broad body of practical wisdom, what makes it into the corporate resilience sphere is often just superficial snippets focussing on the dichotomy of control.

Here’s a small selection of common quotes to that you may have seen.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger; Roman Stoic philosopher and statesman. 4 BC – 65 AD

- “We are more often frightened than hurt; and we suffer more in imagination than in reality.”

- “How does it help…to make troubles heavier by bemoaning them?”

Epictetus; Greek Stoic philosopher. 50 – c. 135 AD

- “It isn’t the things themselves that disturb people, but the judgements that they form about them.”

- “If you want something good, get it from yourself.”

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus; Roman emperor and Stoic philosopher. 161 to 180 AD

- “You have power over your mind – not outside events. Realise this, and you will find strength.”

- “Very little is needed to make a happy life; it is all within yourself, in your way of thinking.”

- “External things are not the problem. It’s your assessment of them.”

As you can see, they espouse the idea that suffering is a subjective experience that a disciplined mind can control. In other words, suffering is a choice. Therefore, don’t waste your time or energy on the external world; instead, focus on managing your inner world because therein lies your salvation. It’s a powerful and enticing message.

Fast forward almost two thousand years, and psychiatrist Dr Albert Ellis and psychotherapist Aaron Beck were rekindling these ancient principles of wisdom in the form of Rational Emotive Behaviour Therapy (REBT) and Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), respectively.

CBT focused on interrogating and correcting irrational thought processes to promote adaptive behaviours. It was fast, effective, and practical, making it eminently more marketable to the time poor masses.

CBT gelled well with 1960s industrialised cultures because it eschewed the slow and meandering explorations of the subconscious made famous by pioneers like Freud and Jung. Instead, it focused on interrogating and correcting irrational thought processes to promote adaptive behaviours. It was fast, effective, and practical, making it eminently more marketable to the time poor masses.

A decade later, researchers were trying to explain the variance in the emergence of psychopathology in children following traumatic events. These studies would become foundational for the field of psychological resilience. While the researchers did recognise environmental contributors, limitations in the research methodology of the time forced them to focus primarily on individual factors. And thus, the die was cast.

Not long after, other researchers such as Bronfenbrenner pointed to this bias and the need to take a more expansive view of resilience; however, much as before, the conversation gravitated back towards individual factors for the sake of simplicity.

Credit: Olivia Guy-Evans on SimplyPsychology.com

Despite growing interest in the field, the corporate world still held psychology at arm’s length until the end of the 20th century. Partly this was due to ignorance, and partly because of the stigma surrounding mental illness. That all changed when positive psychology arrived on the scene in the early 2000s. Finally, psychology had a good news story, one where individuals could become fitter, stronger, happier, and more productive. By the early 2010s, the Lifehacker subculture in Silicon Valley was going mainstream with promises of a hyper-productive techno-utopian future fuelled by optimised minds. It was an exciting story, and the business world lapped it up — workplace wellbeing was about to enter its golden era.

How did Workplace Resilience Lose its Way?

To understand the roots of workplace resilience’s current conundrum, we must return to ancient Rome. It was a “time of universal fear and bondage”, noted the philosopher Hegel. In this oppressive, unpredictable and dangerous environment, Stoicism served as a coping mechanism to retreat into one’s mind and escape the brutal, inflexible realities of the external world. Put bluntly, Hegel argued that a Stoic mindset is a symptom of slavery.

Stoicism served as a coping mechanism to retreat into one’s mind and escape the brutal, inflexible realities of the external world.

Two millennia later, as the world plunged into war and totalitarianism once again, the Stoic’s message was echoed by psychiatrist and concentration camp survivor Viktor Frankl “When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

In the more peaceful and permissive decades that followed (at least in WEIRD cultures: Western, Educated, Industrialised, Rich and Democratic), CBT co-opted and adapted this ‘dichotomy of control‘ principle. What resulted was a slightly tamer version to help people facing challenging situations. At its core, it instructs you to focus on what you can control in the world and what you can’t, then prioritise accordingly. This approach proved both efficacious and efficient, and by the turn of the 21st century, CBT was rapidly establishing itself as the dominant form of therapy. Simultaneously, businesses everywhere were investing in building resilient workers, the economy was booming, and all was looking rosy.

“When we are no longer able to change a situation, we are challenged to change ourselves.”

~ Viktor Frankl

Then, in the latter half of 2007, the economic bubble burst, the GFC followed, and so did the finger-pointing. Then-Federal Reserve Board chairman Alan Greenspan famously blamed the unfounded confidence of investors in his “irrational exuberance” speech. Around the same time, Barbara Ehrenreich (who recently passed away, vale Barb) took to skewering the positive-psychology industry with her 2009 book Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America.

Slowly but steadily, people were starting to wonder, “is there such a thing as being too positive?”

Slowly but steadily, people were starting to wonder, “is there such a thing as being too positive?”. Of course, the ancient Stoics would have most certainly agreed, their message was less about positivity and more about equanimity, but by that stage, Positive Psychology and Personal Resiliency were wedded together in the eyes of consumers. Researchers on both sides argued back and forth about the merits of workforce resilience training; meanwhile, in company lunchrooms, internet forums and Facebook groups, a groundswell of cynicism was brewing.

At the core of the issue was a sense of injustice. Employees were being told how to “toughen up”, yet little was being done to improve organisational processes or workplace conditions. Perhaps the peak of this was the public outcry over Amazon installing “Wellness Chambers” at their warehouses amid claims of inhumane working conditions. The staff sardonically referred to them as “Crying Booths”.

Precisely because the stoic retreats to their own thought, the stoic is more susceptible to external orders imposed on them. As their minds become more and more impervious to the misfortunes of life, they lose the will and the ability to positively and concretely assert themselves.

~ Feihu Yan

In retrospect, the cause was simple to determine; resilience training was faster, cheaper and more straightforward than trying to make structural changes at an organisational level. Add to that the pressures of competing in a tight market, and it was easy to see why most businesses decided to kick the can down the road and hope workers could carry the load.

“Show me the incentive; I’ll show you the outcome.”

~ Charlie Munger

The Covid pandemic pushed that model well beyond breaking point as people exhausted their mental and physical surge capacity. Then came the waves of “languishing“, then “the Great Resignation“, and now “Quiet Quitting“. These are all symptoms of population-scale burnout, to which the only reliable solution is rest, recuperation, and probably a change in work design. However, for those with mouths to feed, mortgages to pay and businesses to run, it’s rarely an option. If that’s you, I say this; if you’re still standing, you don’t need to become resilient; you already are a living, breathing example of resilience.

If you’re still standing, you don’t need to become resilient; you already are a living, breathing example of resilience.

Workplace Resilience is Dead, Long Live Workplace Resilience

At this point, you’d be forgiven for thinking that workplace resilience should be relegated to the history books as yet another fad – not so fast.

The evidence is clear that having a robust sense of ‘internal locus of control‘ is one of the best predictors of positive lifestyle outcomes, from mental and physical health to finances and relationships. Basically, the Stoics amongst us do live happier, healthier, and longer lives.

Thus, it stands to reason that there is real value in strengthening personal resilience. So how do we reconcile this conflict?

It’s time for us to step back and see the broader picture of resilience. It’s time to think like an ecologist.

“A bad system will beat a good person every time.”

~ Edwards Deming

What Can Ecology Teach Psychology About Resilience?

Medical, psychological and social sciences tend to see the world as a collection of systems and subsystems. e.g. A human is a system made up of a circulatory, endocrine, and nervous system (to name but a few). However, this reductivist approach never entirely accounts for what we observe in reality. In defence, we tend to dismiss this incongruence and declare, “The whole is more than the sum of its parts”. But, as systems theorist Dr Derek Cabrera warns, this is a risky cop-out. The truth is this; the whole is precisely the sum of its parts; we’re just missing crucial information.

Ecologists eschew the reductivist approach and instead try to view things as holistically as possible. Instead of multiple systems, they see one system – the ‘everything system‘ – in which different layers or ‘scales’ interact with one another. Bronfenbrenner would be proud. In addition, there is much more attention paid to relationships because they’re the invisible threads that form the fabric of reality. It’s a deceptively simple yet powerful mental flip.

From this perspective, we can begin to see why bolstering individual resilience while ignoring the other scales was doomed from the start. We currently have a front-row seat to see how this is jeopardising entire industries (health care, aged care, and education are obvious examples). In turn, this can destabilise the viability of a whole society.

Conversely, this framing also reveals new ways of shaping organisations and societies that mimic living systems with embedded multisystemic resilience.

How Can You Build Multisystemic Resilience in Your Workplace?

Dr Michael Ungar has done more than most in bridging the worlds of Biological, Psychological, Social, and Ecological resilience to create a term he refers to as Multisystemic Resilience. In it, he lays out the following seven principles:

- Resilience occurs in contexts of adversity

- Resilience is a process

- There are trade-offs between systems when a system experiences resilience

- A resilient system is open, dynamic, and complex

- A resilient system promotes connectivity

- A resilient system demonstrates experimentation and learning

- A resilient system includes diversity, redundancy, and participation.

So, let’s look at what that might look like in the world of work.

1. Resilience occurs in contexts of adversity.

Ungar describes resilience as something that can only emerge once the system and the threat interact. No threat; no resilience. What’s more, the stress needs to be atypical. This suggests that the typical image of a person or a business soldiering on against the same old problems is not a sign of resilience. Rather, the lack of learning and adaptation indicates a deficiency in resilience. This highlights the common confusion between grit (soldiering on) and genuine resilience.

Logically then, since resilience is a response to atypical stress, we should expect resilience to look different with each new threat.

The typical image of a person or a business soldiering on against the same old problems is not a sign of resilience. Rather, the lack of learning and adaptation indicates a deficiency in resilience.

2. Resilience is a process

Depending on who you ask, resilience is a trait, or an outcome, or a process. From my experience, basically everyone speaks of it as though it’s a trait. e.g. “They’re a very resilient person.” (The exception to this are certain psychologists and people who specialise in human resilience.)

Conceptualising resilience as a trait tends to ignore context and lure people into ‘fixed-mindset’ thinking. I’m confident most of us can think of people in our lives who seem highly resilient in one scenario (e.g. high-pressure job), but fall apart in another (e.g. relationship break-up). Resilience then, is not solely inside people or things; it emerges between the system and the threat. Nevertheless, there’s still a dominant narrative that resilience is some kind of ‘returning’ to a homeostatic baseline after adversity. In other words, recovery.

Ungar’s ecological concept of resilience is much broader than just recovery. It also includes; persistence, resistance, adaption, and transformation.

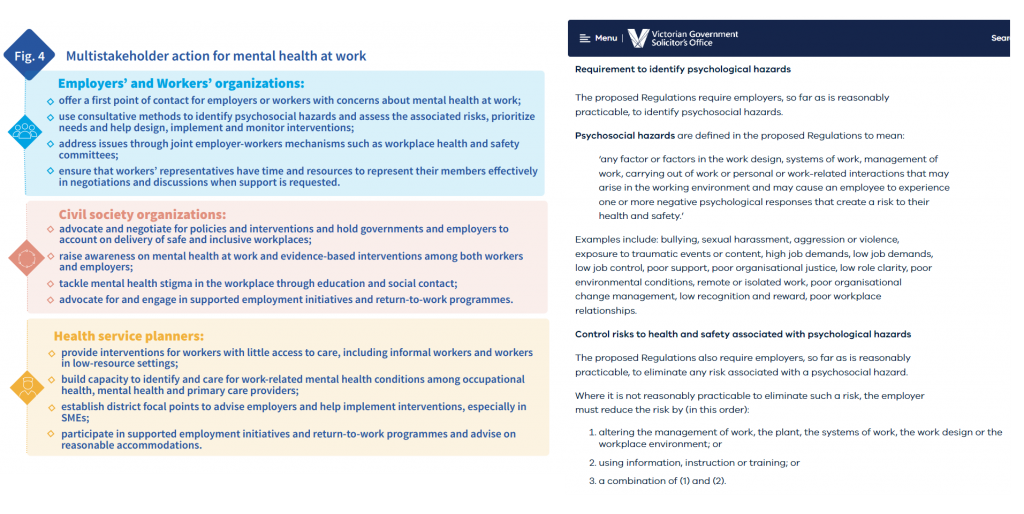

- ‘Persistence‘ describes how other scales can protect a particular scale within the system. For example, in a healthcare setting, surrounding doctors and nurses with dedicated support teams to reduce their admin burden may reduce burnout and medical errors, leading to greater resilience for the hospital and, in turn, the healthcare system. More generally, Australia’s recent raft of legislation requiring employers to identify, eliminate or mitigate psychosocial hazards at a systemic level is another example of how multisystemic resilience reduces victim blaming.

B: Following NSW and Western Australia’s lead in enacting codes of conduct around a systemic approach Psychosocial Risk Management at work, Victoria has taken it up a notch and is about to legislate it.

- ‘Resistance‘ is similar to persistence, but it describes fending off the threat so that the current way a scale operates doesn’t need to change. A recent real-world example was the government funding salaries of cafes and restaurants during the lockdowns. This allowed them to continue operating and stave off financial ruin.

- ‘Adaption‘ occurs when the system accommodates the stress in order to mitigate its impact. In the face of increasing burnout, one could imagine shorter work weeks or increasing employees’ autonomy. Short-term productivity might drop, but by reducing talent attrition, the likelihood of long-term sustainability of the organisation increases.

- ‘Transformation‘ requires broader, fundamental shifts to new ways of operating. The transition to hybrid work forced by the pandemic has been a good test case. It revealed which companies wanted a return to ‘business as usual’ and those that leaned into the future. This further impacts the functioning and structure of society, potentially reducing our environmental impact and, in turn, the sustainability of the ‘entire ecosystem’.

3. Trade-offs between scales

In the ecological model, scales can interact in mutually beneficial ways; however, there may be situations in which one scale will need to sacrifice in order to maintain the viability of the whole system.

Our response to COVID provides a practical working model. The pathogen was a biological threat. To protect our biological scale, our social and psychological scales were sacrificed in lockdown efforts. The question we face now is how to restore those scales, which will inevitably raise the risk to our biological scale. Getting this mix of trade-offs between scales right is a continual delicate dance.

4. A Resilient System Is Open, Dynamic, and Complex

Ecosystems are energy transfer systems. The more closed, stable and simple a system is, the less life it has flowing through it and the slower it is to adapt.

On the flip side, the more energy available, the greater the scale and complexity that can arise. That allows for faster adaption but also invites greater competition and disruption.

E.g. on an arctic rock, you may find a lonely layer of lichen that only grows a millimetre a year. Compare that to a tropical rainforest, replete with rich soil, abundant sunlight and water, and growth is explosive. The catch is that life in the rainforest is often short and brutal, whereas the lichen lives for centuries largely unchallenged (excluding the odd nibble from a reindeer).

The more closed, stable and simple a system is, the less life it has flowing through it and the slower it is to adapt.

As a business, you need to ask yourself, does your market look more like an arctic rock or a rainforest? If it’s the former, ‘business as usual’ is fine (though I’m stumped to think of a market that is not experiencing disruption these days). If it’s the latter, long-term viability will only be possible if you continually hunt for new information and increase your capacity to obtain the resources and know-how to deal with the continual barrage of novel threats.

This is one key reason psychological safety is more important than ever because threats and opportunities need to be identified as early and often as possible. That can’t happen if people are afraid to speak up.

5. A Resilient System Promotes Connectivity

Arguably, the strongest predictor of someone’s ability to overcome adversity boils down to two things: Firstly, they have a social support network (family, friends, community). Secondly, they reach out for help when they need it.

This same principle extends to all scales of a system. For example, history is replete with examples of nations that were isolated (either self-imposed or land-locked) and subsequently withered.

Fundamentally, connectivity allows for resource sharing. While organisms do compete with one another, there is also a level of cooperation. In forests, fungal mycelia create vast webs connecting all plants. Helping out your competitor mightn’t sound like a smart strategy, but if it protects the entire forest from desertification, then it’s essential. Such is the wisdom of nature.

A real-world business example of this has been the collaboration among Australian wine producers. Back in the 80s, they agreed to levy themselves and match government funding for research and development. By pooling resources and sharing the resulting innovations, they dramatically increased their return on investment. Within just a few decades, Aussie wine was a respected global player.

Of course, such connectivity does involve a level of vulnerability, but with the proper measures in place, the reward outweighs the risk.

6. A Resilient System Demonstrates Experimentation and Learning

In ecological systems, sensing and responding to threats and opportunities in your environment is key to surviving. Bigger-brained creatures take it a step further by anticipating future conditions and proactively adapting – this is known as allostasis and the inspiration for our company name: Allos.

In short, resilience requires continual learning and adjustment in the face of new information. Of course, the natural human tendency is to simplify as much as possible and focus on working ‘in the business’, not ‘on the business’.

While this helps minimise cognitive overload, there’s a genuine risk of failing to read the tea leaves on major trends and finding yourself or your business obsolete.

Therefore, if you feel like you’re constantly learning and things are never entirely under control, it’s probably a positive vital sign, both for yourself and your business.

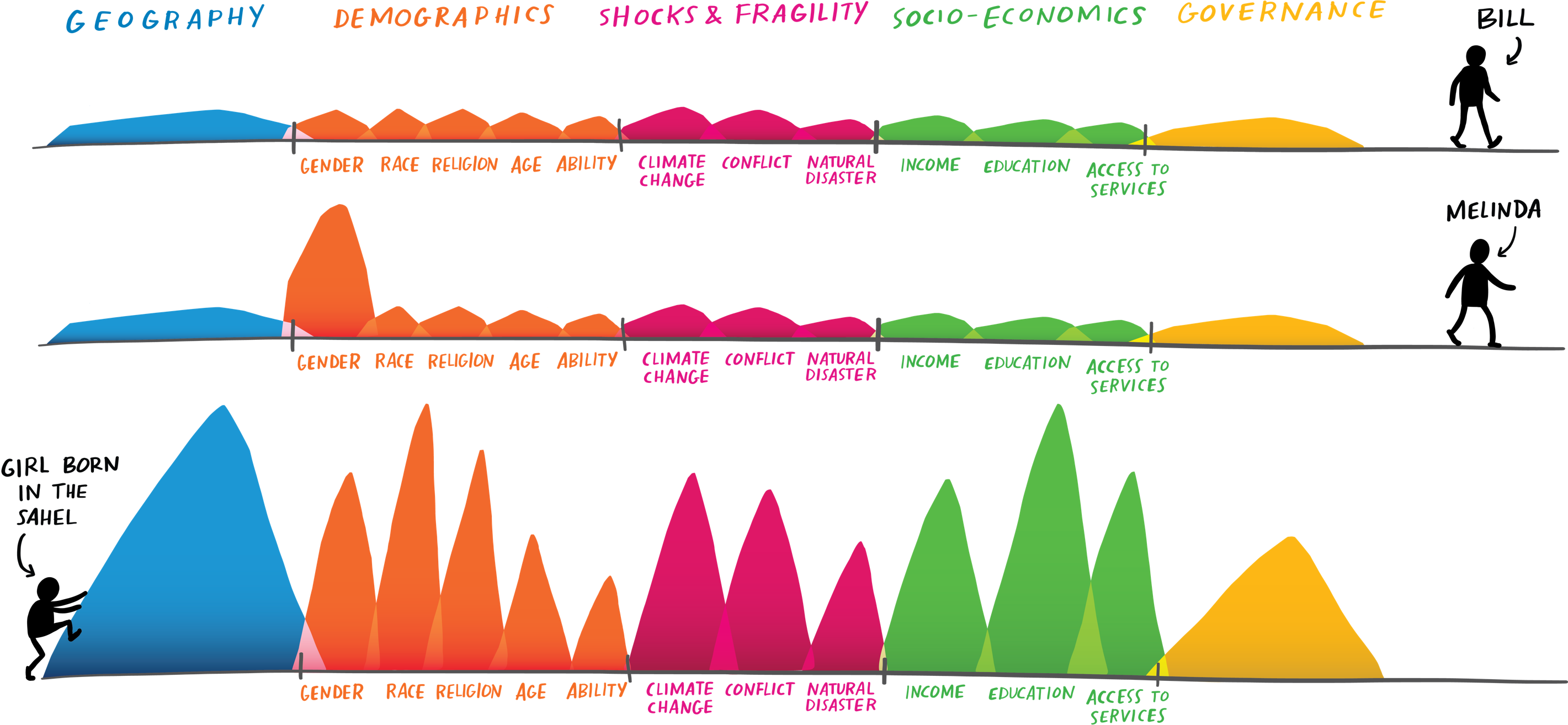

7. A Resilient System Includes Diversity, Redundancy, and Participation

99% of the species that have ever inhabited this planet are extinct. In that way, life really is precious.

A big part of why survival, especially long-term, is so rare is because the natural world is volatile and unpredictable. What’s more, we’re often blind to the role of luck in our success and failure. For example, the single biggest factor determining your health, success, and overall well-being is not your intelligence or willpower; it’s where you were born. This is because countries with more opportunities, open to a broader spectrum of society, and better social safety nets permit risk-taking while reducing the chance of catastrophic failure for individuals. Similarly, a farmer who plants a variety of crops hedges their risk against pests and bad weather.

In short, diversity, redundancy, and inclusion create fail-friendly societies and distribute risk while maximising opportunity. That means we can run multiple experiments within a lifetime instead of experimenting one life at a time. The result; adaptation occurs at the speed of thought.

Is there a future for multisystemic resilience in business?

Ignoring the interrelationships between systems denies the nature of reality and invites disaster – that much is clear.

However, the question remains whether we, as individuals, communities or a species can wrap our heads around this level of complexity, let alone put it to practical use.

To that, I say two things. Firstly, natural selection is unsympathetic. Failure to factor in externalities will likely buy you entry into the 99% extinct club. If it hasn’t thus far, you’re lucky – and luck runs out eventually.

Secondly, don’t confuse complexity for over-complicated – they are two different things.

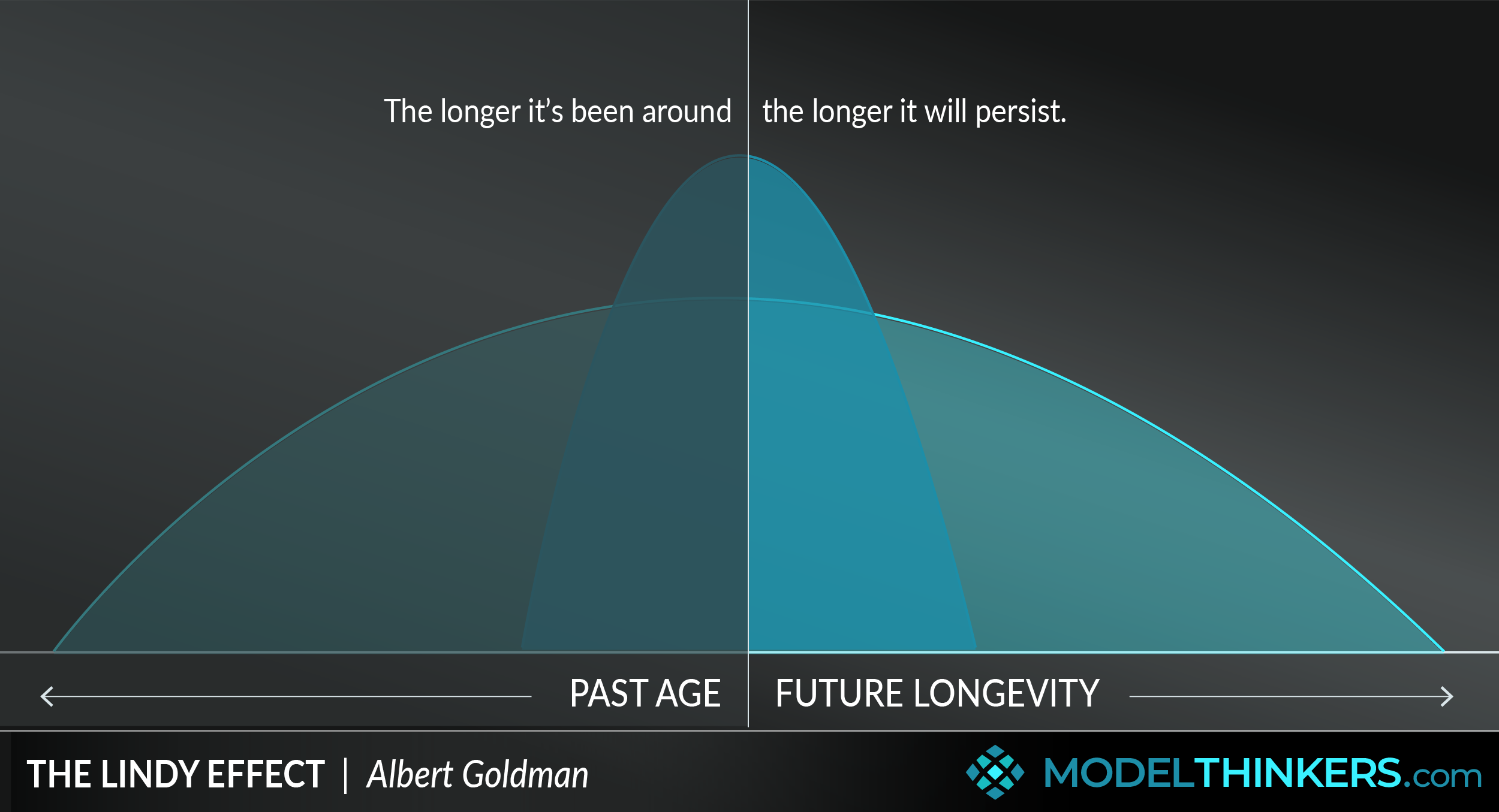

In nature, complex behaviour often emerges from simple rules. See an ant’s nest or a murmuration of swallows. Our job is to determine what those fundamental principles might be. To that end, consider the Lindy effect: the longer something has been around, the longer it’s likely to persist into the future. Therefore, look to the past and see what general principles have stood the test of time. Here in Australia, Indigenous knowledge systems are an obvious wealth of wisdom.

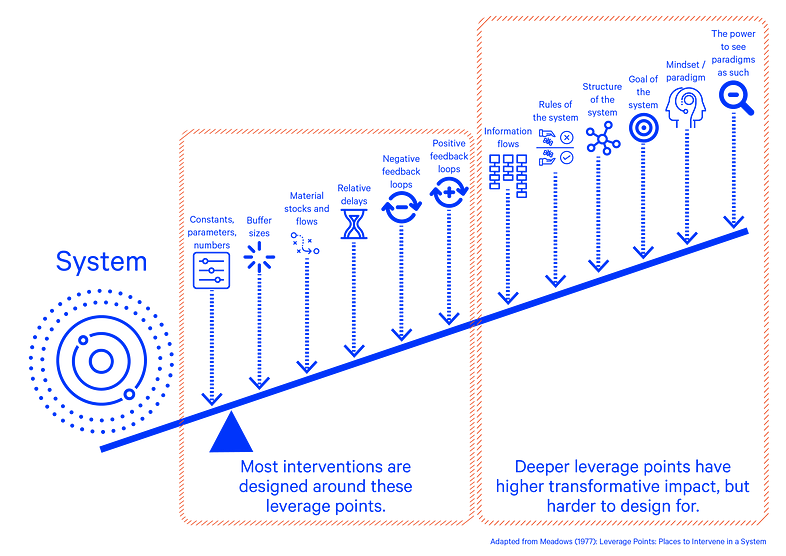

This brings us back to the Stoics. Their ideas have undoubtedly withstood the test of time and will most likely outlive CBT, the field of psychology and maybe civilisation as we know it. But theirs was a world where citizens had little agency over their society. Right now, however, a reasonable proportion of the world’s population lives in participatory democracies with around 75 years of peace under their belt. We’ve never had it so good, and that offers us the luxury of targeting more powerful leverage points in the system that weren’t previously available to us, which, if we get it right, will improve the world of work and the world at large.

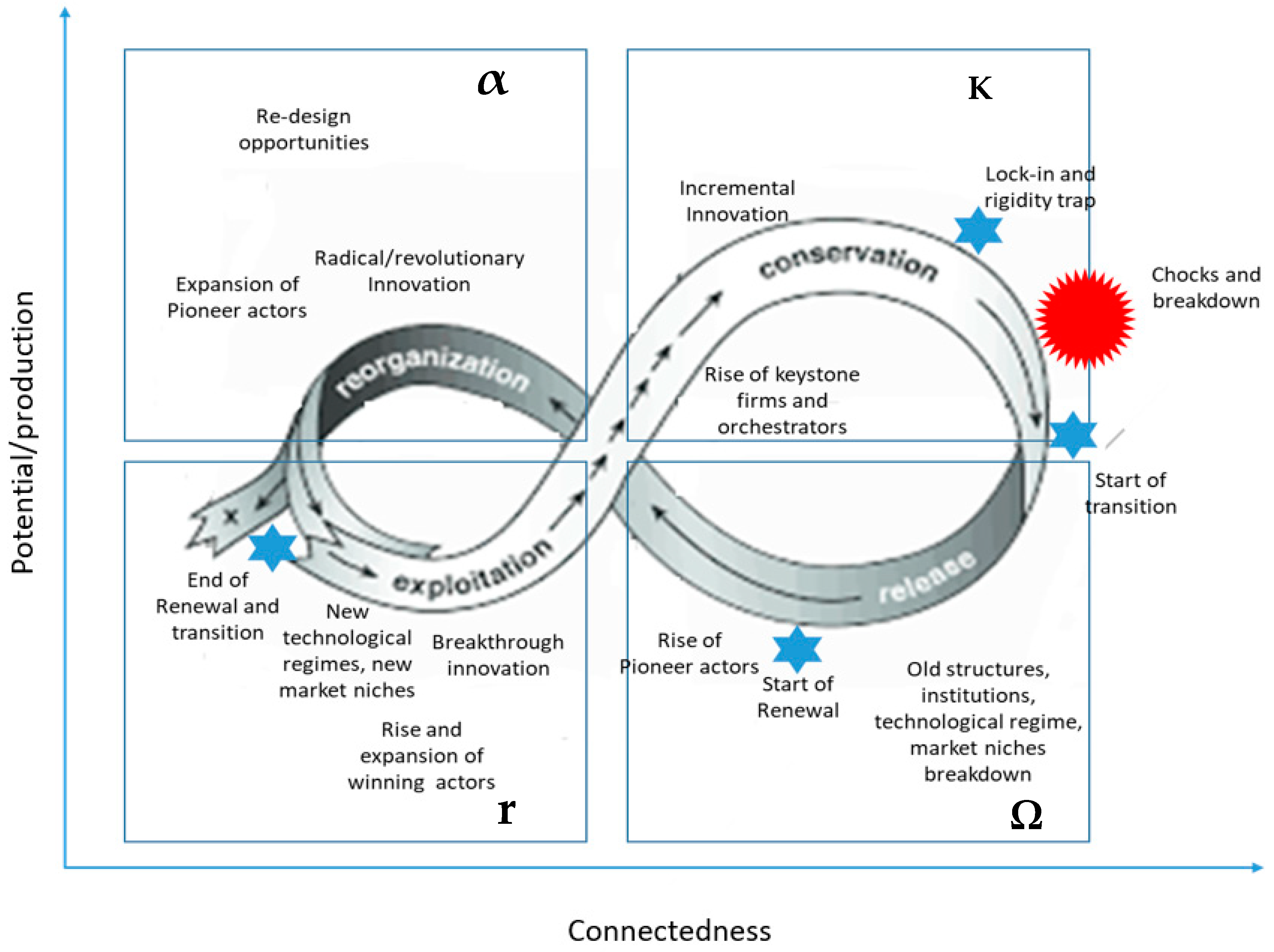

Diagram Credit: Corina Angheloiu Medium

We are living through an extraordinary time in history, and there’s no guarantee it will last. Our civilisation is being strained by the domino effects of energy and food insecurity, climate change, inflation and six-continent supply chain snarls.

Meanwhile, Oxfam’s recent projections suggest that 85% of the world’s population will see healthcare, education, and social protections scaled back in 2023 as austerity measures bite. How will this impact our multisystemic resilience?

When faced with uncertainty and so much out of our control, it’s easy to fall prey to catastrophising. However, the Panarchy model reminds us that the evolution of complex adaptive systems requires the old world to give way to the new, and with that comes the opportunity to rebuild the world anew.

If the future looks all too hopeless and multisystemic resilience seems all too theoretical, I’d like to tell you a story close to my heart. It’s the story of my second home.

A Practical Example of Multisystemic Resilience: How Cable Cars and a Culture of Care Saved the Murder Capital of the World

A striking real-world example of the power of using a multisystemic approach to resilience is the story of the metro system in Medellín, Colombia.

In the decade following Pablo Escobar’s death, a host of gangs were vying for domination of the drug trade, and Medellín quickly earned the grisly title of ‘Murder capital of the world‘. Meanwhile, the world’s second-longest-running civil war raged on in the countryside as left-wing guerilla armies and right-wing paramilitaries clashed (both funded by politicians and the drug cartels). By the early 2000s, the number of internally displaced people (AKA domestic refugees) measured in the millions. The desperate and poor fled to the cities; many to Medellín.

Medellín lies in a valley high up in the Andean mountains — think Switzerland in the tropics. Thus, unable to afford homes in the city proper, the refugees set up camp on the mountain ranges encircling the city. This created a diabolical scenario for the newly arrived; in the centre of the valley, there was relative safety and job opportunities. The problem, one had to cross the gauntlet of gang warfare to get there. Government planners saw the tinderbox that was forming; if they didn’t do something drastic, the refugees would be pulled into the ranks of the gangs, and the city would implode.

A typical reaction in this scenario is for the rich to gentrify their suburbs. However, that approach tends to divide the community further and thus weaken the larger system. So, city planners in Medellín did something bold and brilliant instead; they built a network of state-of-the-art cable cars up to the communities in the mountains. These cable cars then connected to the metro system that ran along the length of the valley floor. Suddenly, the poor and desperate could quite literally float over the violence to jobs in the city. The city then hired architects to design beautiful libraries and cultural attractions which were built in those mountaintop barrios. Following that, they embarked on a community campaign called ‘Cultura Metro’ involving educational programs, art projects and sustainability initiatives. The message it sent to the dispossessed and homeless was powerful; We see you. We care. We are one.

By the time I arrived in Medellín in 2008, the homicide rate had dropped by 80% from it’s peak, making it safer than many US cities. To say cable cars and libraries were the sole reason for Medellín’s transformation would be untrue. Of course, there were other influences at other scales in the system — such is the nature of multisystemic resilience. Nevertheless, I think it is a shining example of the extraordinary potential of thinking systemically and the power of love and hope in overcoming hardship.

“If your choices are beautiful, so too will you be”

Epictetus

One Comment on “How the Workplace Resilience Movement Lost its Way and How to Save it”

Pingback: Q&A: Antony Malmo Discusses Employee Wellness Trends In 2023