In the summer of 1956, a young lawyer was led, handcuffed, into a tiny jail cell devoid of bedding or plumbing. His communication with the outside world was restricted to writing and receiving one letter every six months. He was permitted to receive a single visitor for half an hour, once per year. It would be another 27 years before he would be free again; by then, he would be 71.

You would be forgiven for thinking that no human could endure these conditions for so long and stay mentally intact. However, far from being broken, upon his release, he ran for president, and in doing so, changed a nation. As a child he was called ‘trouble maker’; as a free man, the world knew him as Nelson (Mandib) Mandela.

This level of resilience is hard for most of us to wrap our heads around. It seems super-human for a person to be so impervious to so much social isolation for so long. Yet, Mandela wasn’t impervious. Reflecting on his time in jail, he revealed “I found solitary confinement the most forbidding aspect of prison life. There is no end and no beginning; there is only one’s mind, which can begin to play tricks. Was that a dream or did it really happen? One begins to questions everything.”

“I found solitary confinement the most forbidding aspect of prison life. There is no end and no beginning; there is only one’s mind, which can begin to play tricks. Was that a dream or did it really happen? One begins to questions everything.”

If a person with such mental mettle struggled with solitary confinement, then it’s natural to conclude that for the rest of us, sustained social isolation is a certain recipe for misery. However, if that’s true, how do we explain those who thrive in solitude? What of the monks and sages whom, for millennia, have kept vows of silence perched in their mountain top monasteries seeking enlightenment? Were they all kidding themselves? What’s more, how do we explain the poets, painters, and writers throughout history who sought time alone? And what of the all the farmers and nomads, scattered throughout remote lands? Are they all miserable too?

Clearly, there’s more to the story. As we will see, loneliness and solitude are vastly different experiences with equally different outcomes for our quality of life. Now, as we find ourselves facing lockdown loneliness, trying to avoid the Covid 19 pandemic, perhaps this is a good time for us to examine our relationship with social isolation and what it means for us moving forward.

Loneliness under lock-down

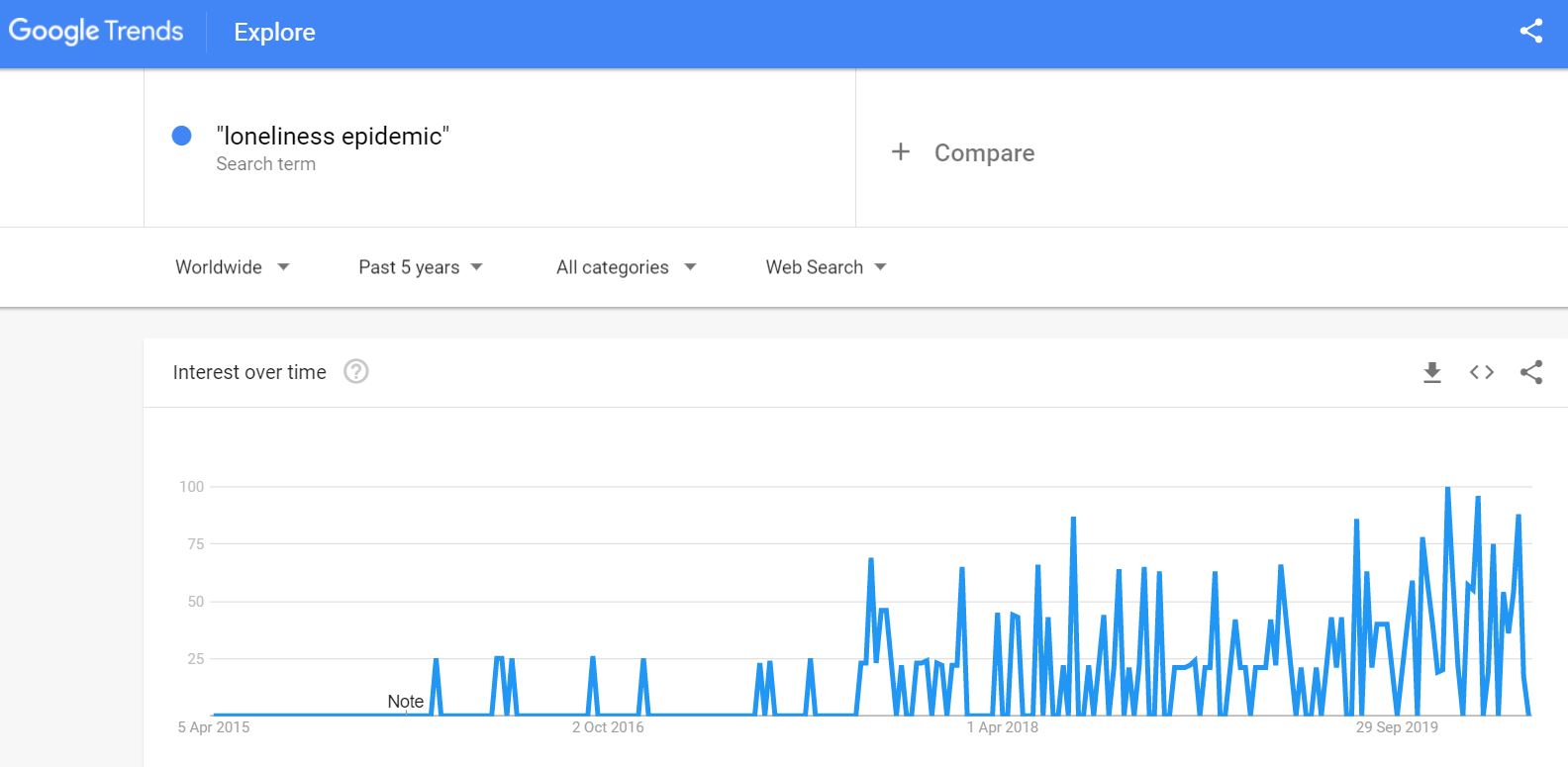

Prior to the takeover of your news feed by Covid 19 pandemic, you may have seen reports stating that we were in the midst of a loneliness epidemic. The UK went so far as to appoint a Minister for Loneliness and there were calls for Australia to follow suit. If the claims of an epidemic are true, we should take heed because social loneliness – to be blunt – is a killer. Yet, while the research clearly demonstrates that loneliness is harmful to individuals, it’s not so clear that there is a loneliness epidemic.

Why the confusion? There are the usual suspects of academic ambiguity; a dearth of research, dubious data and the problematic practice of asking people ‘how they feel’. However, when it comes to loneliness, there is an added layer – it is a fluid concept, and it means different things to different people at different times. Consequently, much of the recent conversation around emotional loneliness is clouded by semantics and cultural conditioning. In other words, it’s unclear that we’re asking the right questions, let alone getting the right answers.

With so many lives at stake and the prospect of months of , and in front of us, it’s important for us to understand how we as individuals, and as a society, can best adjust. Getting it wrong will increase suffering and cost lives; getting it right will save lives and potentially trigger a positive change in how we live our lives post the Covid-19 lockdown.

[activecampaign form=3 css=1]

How loneliness kills

Chronic loneliness, in the USA at least, kills more people than obesity, cancer and heart disease. It’s been shown to reduce longevity more than twice as much as heavy drinking and be as harmful as smoking half a pack of cigarettes a day. But those are just the binary metrics of mortality – there is, of course, the untold emotional torment of feeling lonely. At its most mild, it’s a gnawing sense of disconnection and longing; at its most severe, life is a sea of rejection and suffering where suicidal thoughts take over. The mechanisms by which this occurs are complex and not fully understood; however, at its core lies the fact that evolution wired us to operate in groups and without sufficient social interaction and social support, our mental health declines.

At its most mild, loneliness is a gnawing sense of disconnection and longing; at its most severe, life is a sea of rejection and suffering where suicidal thoughts take over.

Humans haven’t always been apex predators; in fact, for most of our evolutionary history, we were slow-moving, defenceless snacks for bigger beasts. What saved us were our brains, or more specifically, our ability to communicate and coordinate in large numbers. The most elegant evidence for this is Dunbar’s number which predicts the typical group size for different species of primates based on the size of their neocortex (where we do our complex thinking). Humans have the largest neocortex proportional to total brain size of any primate – large enough to handle up to around 150 relationships. This impressive network provided us with an abundance of social support. So, we’re not just social creatures – we’re very social creatures.

True to its name, our nervous system gets nervous when we’re cut off from our tribe. Our fight or flight response is a primitive, yet powerful alarm system that still thinks we’re on the savanna and being alone means getting eaten or certain starvation. Now, while your pantry is full of panic bought tinned-food and there are no lions roaming the streets (unable verify this), being alone – especially at night – triggers that ancient circuitry; our ears prick at the sound of the refrigerator switching on, the creak of floorboards make us jump, we see movement in the corners of our vision. This hyper-vigilance even follows us throughout the night; lonely people have more disturbed sleep – robbing them of its essential restorative effects.

Chronic loneliness triggers a continual stream of stress hormones that erode the machinery of the body and mind; interfering with our immunity, dulling our memories and high-jacking our thoughts. We begin to make more mistakes at work, we get slack about hygiene, we get sick more often, we lose our ability to accurately read other’s intentions, and socialising becomes exhausting. In short, the relentless and causes . We self-medicate with alcohol and drugs to numb the anxiety, consume TV and social media to distract and simulate companionship. Fatigued, foggy-minded, and fearful; we begin to close ourselves off further from the world. Magnifying the risk is the simple reality that if we fall ill or fall from a ladder, there’s less chance that someone will come to our aid. The cruel irony of loneliness is that just when we need to reach out and connect with others most of all, we are the least likely to do so.

The cruel irony of loneliness is that just when we need to reach out and connect with others most of all, we are the least likely to do so.

Thus, just as physical pain aims to protect us from physical harm[1], social pain – aka loneliness – aims to protect us from the risk of isolation. It’s a signal, telling us to return to our tribe.

Alone but not lonely

While it is clear that loneliness can be devastating on an individual level, what is not so clear is whether it warrants epidemic status. The term ‘epidemic’, as Covid-19 has brought into stark clarity, suggests something is spreading rapidly. Therefore, if society is experiencing a loneliness epidemic, the data should suggest a surge in numbers.

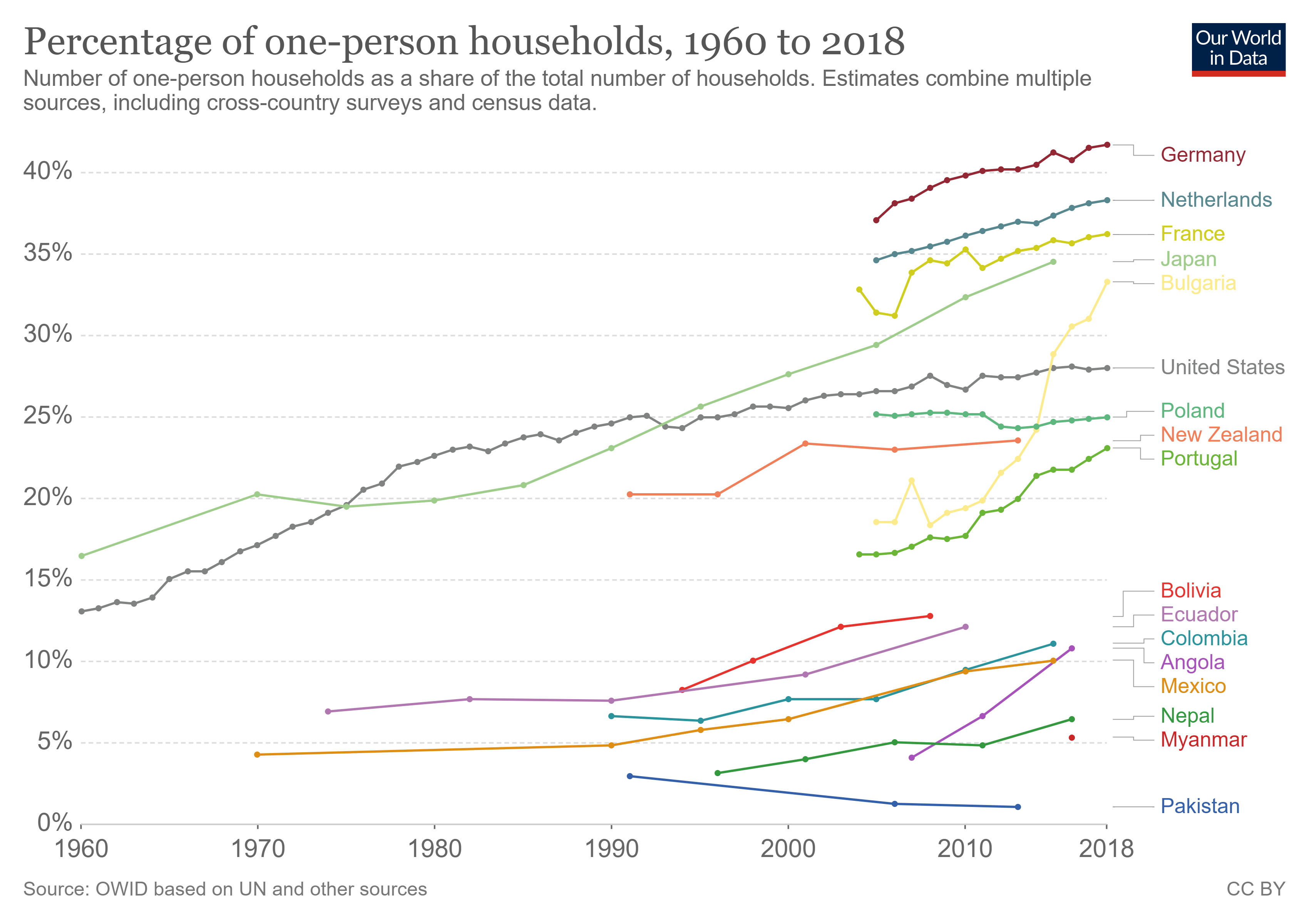

Studies into loneliness do indeed show a surge in numbers; however, what those numbers represent is up for debate. As Esteban Ortiz-Ospina – Senior Researcher at OurWorldInData pointed out, a fundamental flaw in oft-cited loneliness studies is the use of ‘living alone’ as a measure of ‘loneliness’. However, living alone and feeling lonely are not the same thing. As Ortiz-Ospina quite rightly points out, “while it’s true that many more of us are living alone, spending time alone is not a good predictor of whether people feel lonely, or have weaker social support.” The simple fact is, some of us like living alone.

“there is surprisingly no empirical support for the fact that loneliness is increasing, let alone spreading at epidemic rates”

In the eyes of these hard-nosed data wonks at least, “there is surprisingly no empirical support for the fact that loneliness is increasing, let alone spreading at epidemic rates”. It deserves emphasising that Ortiz-Ospina’s analysis does not deny that loneliness is widespread and harmful; rather, he is simply stating that there isn’t sufficient quality data to support the title of ‘epidemic’. In short, we don’t know enough. What is known is that online media loves endorphine-triggering headlines, so perhaps what this does show is that the real epidemic we’re facing is sensationalist journalism.

No such thing as normal

The second problem with investigating loneliness is the bias brought about by cultural norms which assume that solitude is inherently abnormal and must be fixed. Let me show you what I mean. What images come to mind when you hear someone described as a ‘loner’? What do they look like? How do they act? How do they make you feel? My guess is you imagined an odd character, perhaps dangerous, definitely someone to keep an eye on. However, this binary model of normal and abnormal doesn’t stack up to science.

We are conditioned to be suspicious of loners. Song: Tom Waits – What’s he building in there?

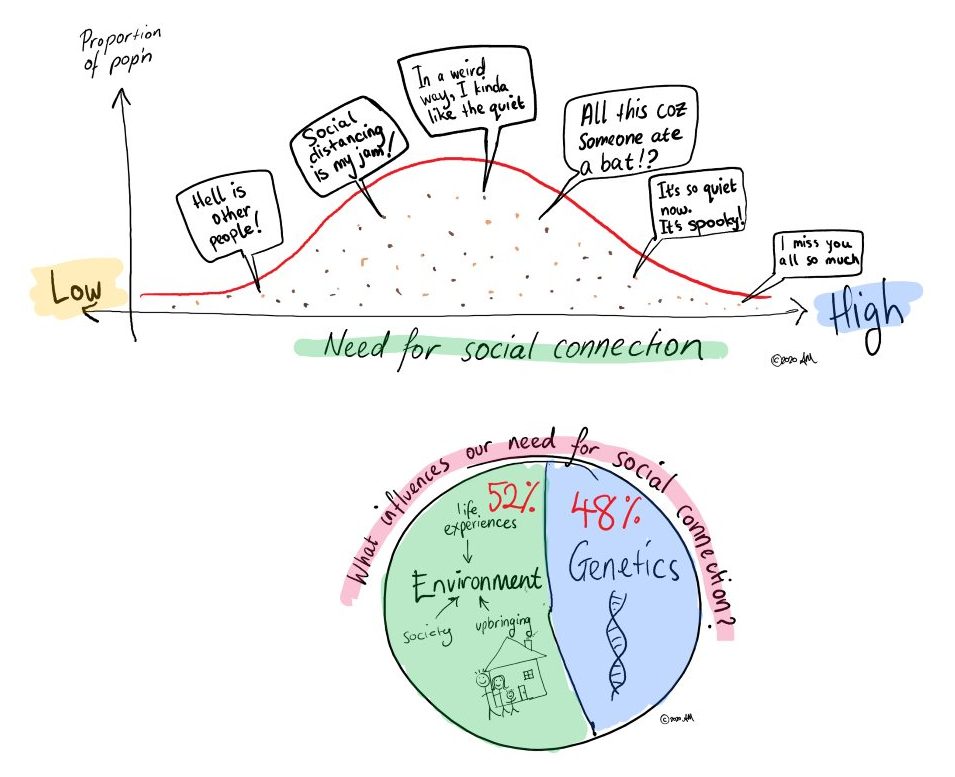

As the late John Cacioppo, a leading researcher in the field of loneliness showed, across any given population of humans, the need for social connectedness varies widely and is driven in large part by variation in our genes. “Some people’s personal need for inclusion or sensitivity to exclusion is low enough that they can tolerate moving away from friends or family without too much distress. Others have been shaped by genes and environment to need daily immersion in close social contact in order to feel okay.”[2] In other words, evolution scatters us across a bell curve; some of us driven towards a nomadic or hermetic life, others towards the constant comfort of others; the rest of us are somewhere in between. Of course, we all have limits, and Cacioppo is quick to emphasise that we all need some level of connection, it’s simply that this threshold varies widely.

“Some people’s personal need for inclusion or sensitivity to exclusion is low enough that they can tolerate moving away from friends or family without too much distress.”

As is so often the case, when we reduce the world to ‘normal’ vs ‘abnormal’ and apply a medical lens, we run the risk of pathologising natural parts of the human experience; the unintended consequence of which is an increase in stigma and feelings of shame for the those who don’t fit the norm. A solution to this oversimplification is to embrace the notion of neurodiversity, whereby we recognise that human behaviours vary widely and that being an outlier isn’t inherently negative.

Indeed, in extraordinary times, extraordinary people can sometimes have an advantage; it’s evolution’s way of spreading its risk portfolio in the face of specific selective pressures. Case in point; depression and disease outbreaks. While depression is generally regarded as a wholly terrible thing, to evolutionary psychiatrists, depression had a surprising upside for our ancestors: it increased survival against our number one killer – contagious diseases.

The theory goes; just as our body responds to the presence of pathogens with inflammation, the mind also has a few tricks up its sleeve. It responds by triggering a suite of behaviours that reduce the risk of further infection, e.g. isolating oneself, eating less, moving less, and sleeping more; behaviours often associated with depression. Seen through this lens, perhaps it’s not so surprising to learn that many key genes responsible for inflammation also code for depression.

While this serves little purpose in our modern world, to our pre-antibiotic ancestors, this response increased their chances of survival. So while our fretting forebears wouldn’t have been happy, they survived, and that’s good enough for evolution. This, in turn, also helps make sense of why, when life’s challenges seem endless and overwhelming – we shut down, hole up in our bedrooms and wish someone could just wake us up when it’s all over.

Covid-19 is a living example of this principle; without strict social distancing measures and enforced isolation, it would have been the extraverts and social butterflies who would have been at increased risk of infection, while the shut-ins and homebodies would have had the competitive edge.

Our immune response can trigger depressive behaviors, which gave our ancestors a survival advantage during disease outbreaks. Source: Miller, A., Raison, C. The role of inflammation in depression: from evolutionary imperative to modern treatment target. Nat Rev Immunol 16, 22–34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nri.2015.5

Not your Grandparents’ loneliness.

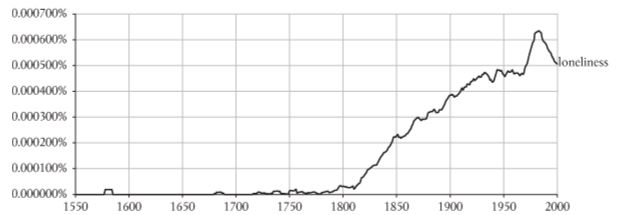

Another curiosity when it comes to loneliness is our changing relationship with it. Cultural historians have suggested that loneliness is a modern invention pointing to the fact that the term ‘loneliness’ is almost impossible to find in any literature prior to the 1800s[3]. Perhaps this was a by-product of our transition from tightly-knit rural communities to anonymous urban environments; however, even once people across the globe started living in cities, our perceptions of loneliness were not uniform.

Graph – Use of the term ‘loneliness’ in literature between 1550 – 2000

Bound Alberti, F. (2019). A Biography of Loneliness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

In the 1940s, social scientists studied the mental associations Germans and Americans had to the experience of solitude[4]. The result; the Germans associated it with positive words such as ‘strong’ and ‘health’, while the Americans associated it with negative words like ‘fear’. Subsequently, when the same studies were repeated decades later, the Germans’ responses had become more pessimistic, just like the Americans. This tells us two things; firstly, that feelings around solitude are culturally dependent; and secondly, that those feelings can change over time.

We can’t conclusively say what drove this change in the German mindset. Still, some point to the influence of Hollywood post WWII whereby US cultural values were beamed into households around the globe thus shifting the window of ‘acceptable behaviour’ to celebrate the extroverts and ridicule the introverts.

If we accept that premise, then the rise of social media is likely turbo-charging the effect. Today, social interaction is measured in the thousands if not millions. Every time we log-on we are subjected to the highlight-reel of other people’s lives; at the beach with friends, a family barbecue, your ex on holiday with their ridiculously gorgeous partner. The message to our brain is clear; everybody is out there having fun together – I should be too. This creates a feedback-gap between expectation and reality, or in modern parlance ‘FOMO’ – Fear of Missing Out, which, in turn, feeds our feelings of loneliness and shame. A 2013 Norwegian[5] study illustrated this in a large-scale longitudinal study of 2000 teens in which researchers studied those who used social networking sites and those that didn’t. What it revealed, somewhat predictably, was that the teens who used social-networking sites had a higher number of social connections and face-to-face contacts; paradoxically, however, they also reported greater feelings of emotional loneliness.

Social media, therefore, cuts both ways; on the one hand, it allows us to expand our social networks, but it creates an unrealistic expectation of reality that our minds find difficult to ignore. While some people suggest taking the nuclear option and disconnecting from social media entirely, a more balanced approach may be to focus on quality over quantity. Remember Dunbar’s number? Well, that 150 person threshold doesn’t mean that we necessarily enjoy all those relationships – we simply have the capacity to tolerate that many. To be happy, most people find 4-6 close friends is sufficient, so perhaps should forget FOMO and embrace JOMO – the Joy of Missing Out on all those unrewarding relationships.

To be happy, most people find 4-6 close friends is sufficient

Research also shows that we experience different levels of loneliness as we age. We tend to assume that old-age is a lonely affair; however, multiple studies from Japan, the US and New Zealand show the opposite is true. Possibly because of a shift in our expectations of the number of friends we need, but also because we learn to become more comfortable in our own company.

The key takeaway here is that the mass self-isolation necessitated by the Covid 19 crisis need not be the wholesale disaster it’s being touted as because we have a degree of control over how we respond. Instead, there are far more significant threats to our mental health emerging; the most ominous of which is job insecurity and financial pressures. Money worries were already the single biggest stressor for Australians prior to this pandemic, and now we face soaring unemployment numbers. Add to that the spike in alcohol consumption and domestic abuse, and we have a perfect storm in the making.

Now, more than ever, we must explore all the tools and strategies at our disposal to navigate the months ahead. Chronic loneliness is a risk we face, but we also have an opportunity to reframe the experience, reduce harm and rediscover the long-lost benefits of positive solitude.

The Case for Solitude

Thus far, I have been using the terms loneliness and solitude interchangeably. However, if you’ve made it this far without noticing, then it goes to show just how blurred these concepts are in our everyday thinking. If we’re going to find ways to thrive, not just merely survive this lock-down, we need to make a clear distinction between these two terms.

Loneliness has its roots in being ostracised – to be cast out from our tribe. It feels as though it is inflicted upon us, punishment for a crime against our people, be it real or imagined. We feel unwanted and worthless, which brings a deep sense of shame. Sometimes, when our transgression is not clear to us, we conclude that it must be who we are as an individual that is the offence and it’s the type of shame that can last a lifetime.

Solitude, in contrast, is an active choice – it is a positive withdrawal from the noise and superficialities of life. It is an opportunity to return to the self, take stock, and maybe – if we’re lucky – grow a little wiser.

While the company of others plays a role, neither loneliness or solitude demand physical isolation. We can feel lonely in a crowd, in fact, sometimes that can be the most devastating type of loneliness – at least on your own you get to be miserable in the privacy of your own home. Conversely, we can find calm solitude sharing a sofa with a loved one and quietly reading. It all boils down to how we frame the experience.

Solitude, is an active choice – it is a positive withdrawal from the noise and superficialities of life.

Positive solitude offers an antidote to the stressed out and distracted lives many of us lead. The problem is, we’re out of practice. Partly this is because it has been stigmatised by popular culture but also because the hyper-connected and frenetic pace of modern life leaves so little time for quiet time. It’s no wonder then that mindfulness meditation is making inroads into clinical psychology and sweeping the business landscape. We are craving a moment to ourselves, to declutter our brains and regain some clarity and control.

By entering into this state of calm reflection, we dial down our fight or flight response (sympathetic nervous system) and engage its counterpart, the rest and digest response (parasympathetic nervous system) which triggers a cascade of restorative physiological reactions from reduced blood pressure and inflammation to improved digestion and immunity.

The great thinkers and innovators of history embraced solitude.

Peace and calm are not the only benefits to our mental wellbeing. When we remove ourselves from the constant barrage of external stimuli, our mind has a chance to wander. As we rummage around in our thoughts, we often stumble upon new ideas and solutions to challenges in our lives. Unsurprisingly, the great thinkers and innovators of history embraced solitude, and it’s a lesson we can all learn from.

To reap the rewards, however, we need to overcome the initial sense of boredom and ignore the impulse to fill the void by turning on the TV or checking our phone. Ironically, the godfather of the smart-phone – Steve Jobs – credited boredom as key to his creativity, explaining that ”boredom allows one to indulge in curiosity and out of curiosity comes everything. All the [technology] stuff is wonderful, but having nothing to do can be wonderful, too.”

we need to overcome the initial sense of boredom and ignore the impulse to fill the void by turning on the TV or checking our phone

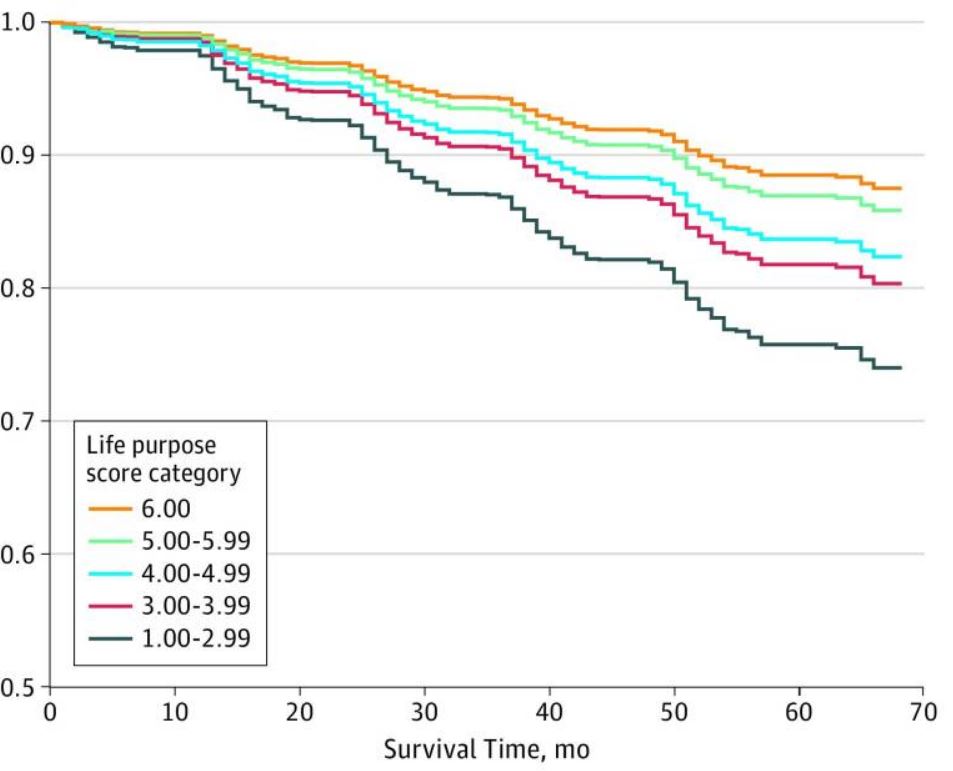

Finally, dedicating time to reflective solitude opens the door to a more meaningful and satisfying life; it creates space where we can contemplate the big questions of life, love, and death. This is more than just a philosophical exercise; making sense of our lives is vital to our own mental health and resilience. The risk we run by ignoring this deep inner work is that we build our sense of identity and self-worth on shallow foundations such as defining ourselves by our job title or romantic relationships. Then, when life inevitably takes those foundations away, we are cast adrift, and our lives suddenly become bereft of meaning and purpose. This isn’t just painful; it can be fatal.

A study of 6985 adults showed that life purpose was significantly associated with all-cause mortality.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6632139/

Today, as so many of us face unemployment as well as the fragility of existence, it’s more important than ever that we make peace with ourselves, and we can’t do that unless we’re willing to sit down with ourselves and have good old heart-to-heart.

What does Successful Solitude Look Like

Finding time for quiet reflection in our otherwise busy lives can be profoundly restorative, but for many of us, it’s not something we’re used to. So what does successful solitude look like? In the words of Rae Andre, Organisational Psychologist and author, positive solitude requires “space – any space – that does not demand a reaction on your part. Feeling compelled to act, to do something, is what disrupts solitude”.[7]

Based on this broad definition, anything from knitting to watching the tide roll in fit the bill, so long as its sufficiently leisurely. While the evidence is coming in thick and fast as to the benefits of journaling, mindfulness meditation, and spending time in nature (2 hours per week is the recommended minimum dose), there’s little research as to what other activities deliver the best results. But perhaps that’s part of the charm – positive solitude is the antithesis of ‘achieving’, ‘optimisation’, ‘efficiency’ and all those other buzzwords synonymous with the relentless pressure of the modern world. Instead, it is permission to partake in seemingly pointless activities without judgment. In short – it’s freedom for your brain to be its irreverent, irrational self.

Positive solitude requires space – any space – that does not demand a reaction on your part.

The dose makes the poison.

The lack of a rule book notwithstanding, we should remember that while solitude offers tremendous benefits, the flip-side is we could wind up alone and lonely. Therefore, we would be wise to learn from those who have made it their vocation.

Monks are often portrayed as robed ascetics sitting alone on a mountain top, but historically this has been the exception rather than the rule. Instead, religious traditions from Asia to Europe have a strong element of community practice where monks cycle between isolation and communal living.

Religious traditions have a strong element of community practice where monks cycle between isolation and communal living.

In the eyes of neuroscience, this is a sensible system which mitigates the risk of damage to our memory and learning brought about by extended sensory deprivation. At the same time, having others nearby helps to reduce triggering our fight or flight response as our subconscious knows we’re not truly alone. Additionally, they were not sitting about daydreaming aimlessly. Instead, they maintained routines, kept themselves fed and exercised. What’s more, they received continual guidance on navigating their thought processes, focusing on concepts such as gratitude and compassion, two practices that have been shown to improve mental wellbeing in modern clinical settings.

If the practices of spiritual renunciation give us an indication of best practice, the lives of artists provide plenty of warning posts. Of course, not all artists choose a life of solitude, and plenty of artists are healthy and happy; nevertheless, the numbers cannot be ignored. Those employed in the arts are four times more likely to die from suicide. Determining whether this is correlation or causation can be tricky; is it something about the creative mind that predisposes artists to poorer mental health or is it the solo path they lead? Perhaps it’s the unstable employment, insatiable audiences, obsessive dedication, or imposter syndrome? There is no overarching explanation.

Nevertheless, each of these factors is worth watching out for, and as a society, it’s something we cannot ignore any more. Given how much joy artists brings into our lives; every movie, song, novel, poem and painting; they deserve better than to be dismissed with the ‘tortured artist’ cliche.

It’s a similar conundrum for farmers. I grew up farming and often long for the freedom of wide-open spaces and communion with nature. But, if I’m honest with myself, I also remember that as a teen, I was always envious of the town kids who would hang out after school, riding bikes and kicking the footy. My feedback-gap was substantial, and the loneliness was often unbearable. As soon as I could, I fled to the city and never turned back. I wasn’t alone; farming townships across Australia are shrinking and disappearing from the map, and with it, the loneliness buffering effects of community.

Intriguingly, the underlying rates of mental illness amongst farmers are not substantially different from urban dwellers[8], yet suicide rates are far higher[9]. How can this be? Some posit economic insecurity and the greater access to firearms; however, there is one other pattern that we shouldn’t ignore; the more remote a farm is, the less mental health services are available[10]. Put simply, when farmers need help, they often can’t get it.

We need to carve out time for ourselves to let go of the demands placed on us by the world.

So what have we learned? Firstly, positive solitude is no substitute for the pillars of wellbeing; physical exercise, eating well, financial stability, and proactive mental wellbeing. So long as we’re not neglecting those, we can begin to experiment with solitude. Ideally, we need to carve out time for ourselves to let go of the demands placed on us by the world. Once there, we need to embrace the nothingness and if we’re in the mood, ponder the deeper questions of life. There is great benefit in practising it alongside others, but we can also do it in isolation if we prefer, we just need to remember to check-in with others from time to time. In essence, solitude is self-care.

Will Covid 19 restrictions cause a loneliness epidemic?

Right now, practically every home in Australia is under lock-down. Globally, at least another billion are following suit, and it looks as though this will continue for the foreseeable future. So will this trigger a genuine loneliness epidemic? To a degree, yes, but it may not be as ruinous as the newspaper headlines suggest. Here’s why.

Our collective response to Covid-19 has been an inspiring demonstration of camaraderie en masse.

Firstly, we’re all in this together. Consequently, this isn’t a case of ostracisation. This is vitally important because if you remember back to the defining qualities of loneliness – it’s about feeling shamed and shunned by your tribe. If anything, our collective response to Covid-19 has been an inspiring demonstration of camaraderie en masse. We have seen this ‘uniting for a common cause’ throughout history in the face of existential threats like war and natural disasters. Yes, we suffer, but we suffer together, and that makes all the difference.

Second, if we return to Cappioco’s bell-curve for solitude tolerance; it’s true that those who crave constant companionship will struggle most. However, the lone-wolves at the other end of the spectrum will carry on largely unaffected. For the vast majority of us who lie somewhere in between – we are going to feel a range of emotions, but we also have choices.

The first choice we have is to close our expectation vs reality feedback-gap. If news, social media, or the stories we tell ourselves are making us miserable, we can tune out or choose to rewrite those stories. Is it easy? In principle, yes. In practice, not so much. Such is the nature of addiction. But if we consider the consequences and commit to taking charge of our lives, we’re far more likely to succeed.

The next decision we need to make is how we respond to this isolation. We can either wallow, wishing the world was different, or, we can use this as an opportunity to discover the therapeutic and enriching qualities of positive solitude. By being intentional about creating space for our minds to wander and ponder, there’s a good chance we will emerge from our isolation a little more grateful, compassionate, wiser, and at peace with ourselves.

[activecampaign form=3 css=1]

[1] John T. Cacioppo, William Patrick – Loneliness_ Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection (2009)

[2] John T. Cacioppo, William Patrick – Loneliness_ Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection (2009)

[3] Bound Alberti, F. (2019). A Biography of Loneliness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[4] André, R. (1992). Positive solitude: A practical program for mastering loneliness and achieving self-fulfillment. New York, NY: HarperPerennial.

[5] Amichai‐Hamburger, Y. and Schneider, B.H. (2013). Loneliness and Internet Use. In The Handbook of Solitude (eds R.J. Coplan and J.C. Bowker). doi:10.1002/9781118427378.ch18

[6] Alimujiang A, Wiensch A, Boss J, et al. Association Between Life Purpose and Mortality Among US Adults Older Than 50 Years. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e194270. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.4270

[7] André, R. (1992). Positive solitude: A practical program for mastering loneliness and achieving self-fulfillment. New York, NY: HarperPerennial.

[8] Brew, B., Inder, K., Allen, J., Thomas, M., & Kelly, B. (2016). The health and wellbeing of Australian farmers: a longitudinal cohort study. BMC public health, 16, 988. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3664-y

[9] Judd, F., Jackson, H., Fraser, C., Murray, G., Robbins, G., & Komiti, A., (2006), Understanding suicide in Australian farmers, Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology 41 (1), 1-10.

[10] Meadows GN, Enticott JC, Inder B, Russell GM, Gurr R. Better access to mental health care and the failure of the Medicare principle of universality. Med J Aust. 2015;202(4):190–4.