Take Two Friends and Call Me in the Morning.

There’s a little town in England that’s done a remarkable thing. In a reasonably short amount of time, the township of Frome has been able to reduce emergency hospital admissions by 15%. Meanwhile, hospital admissions in neighbouring towns rose by 30%. What is Frome’s secret life-saving technology?

The local medical practice in Frome implemented an interconnected system of medical practitioners called ‘health connectors’ and local volunteer ‘community connectors’ with the help of Compassionate Communities UK. With this innovative approach, more residents were visited, more often. What’s more, these weren’t simply brief medical check-ups; they focused on making time for human connection, a chance to sit and chat with individuals.

This approach has been given the clinical title ‘social prescribing‘, and while – as a tribal species – sharing personal stories is not new to humans, in an age of hyper-individualism and isolation, it’s a revolutionary act.

Social prescribing stimulates something powerful in people; connection and belonging. As the research literature grows, it’s establishing itself as one of the most powerful preventative interventions available; beating out smoking cessation, cutting alcohol, or reducing obesity.

“Social connectedness has a bigger impact on health than giving up smoking, reducing excessive drinking, reducing obesity and any other preventative interventions.”

Compassionate Communities UK

One of the best things we can do to relieve anxiety and depression is to help someone else

Social prescribing is powerful, but the full health potential of connection and belonging comes when all community members reach out and demonstrate care for one another. It’s when friends, families and neighbours help out with everyday tasks and share life events. It’s not rocket science, but it does seem we’re a little out of practice.

The lessons from Frome are manifold and should be a wake-up call for us all. A 2015 meta-analysis showed isolation increased mortality in test participants by 29%. And the impact isn’t just limited to lifespan; it also affects the quality of our day-to-day lives. Prior to the pandemic, an estimated 2.7 million Australian’s experienced anxiety each year, and 1.1 million experienced depression, and it’s well established that isolation and social disconnection feed those conditions. Conversely, research shows that one of the best things we can do to relieve anxiety and depression is to help someone else. Thus, the first obvious benefit of belonging to a community is that you have daily opportunities to help others, and in doing so, get out of your own head. What’s more, when we’re part of a group, we tend to regulate each other’s emotions; if one person in your group is having a bad day, others will probably be having a great day, and because thoughts and feelings are contagious, we balance each other out. Finally, knowing that you helped someone else is a rock-solid reminder that you matter to the world, a feeling often absent in the depths of depression.

Knowing that you helped someone else is a rock-solid reminder that you matter to the world, a feeling often absent in the depths of depression.

In short, human history has always involved uncertainty and suffering. The only difference between then and now is that now more of us are trying to do it alone. We do so at our peril.

Rejection Makes Us Cold-hearted

Social connection impacts more than just thoughts and feelings; it has a profound physical impact too. At some point in our evolution, the brain circuitry responsible for processing physical pain was co-opted by the processes responsible for monitoring social relationships; as the theory goes, those who wandered too far from the tribe were eaten by predators or starved, the survivors – our ancestors – were wired more strongly to stay together. The result is that our sense of connection to others is so tightly woven into our pain perception that the pain of a broken heart and a broken bone feel equally real.

Broken hearts are not limited to romantic relationships gone sour. Any type of perceived rejection, be it social rejection or low social status, triggers the same circuitry and drives feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, and helplessness. Interestingly, our emotional pain response mimics our physical response; in the event of a sudden, sharp injury – we go numb. The somewhat disturbing consequence of this defense mechanism is that people who experience social rejection show less empathy. It doesn’t take too much foresight to see how social disconnection leads to reduced empathy towards others, and in turn, further disconnection. Taken to the extreme, this negative feedback loop can send whole societies into a spiral of distrust and division.

Our sense of connection to others is so tightly woven into our pain perception that the pain of a broken heart and a broken bone feel equally real.

Political Parasites

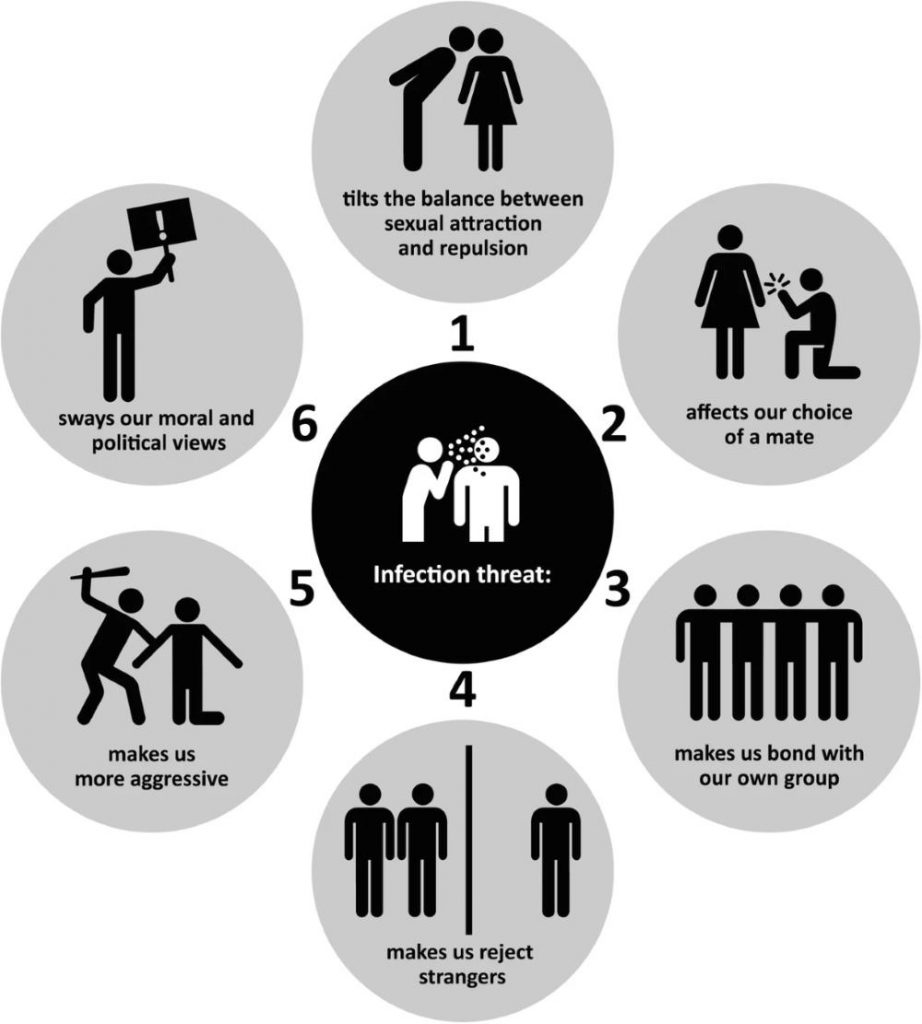

When the pandemic took hold, we were told this would be our generation’s great moment of unity. However, behavioural immunology researchers wouldn’t have been so optimistic because they know how the threat of infection skews our thoughts and behaviours.

Disease, you see, triggers one of our oldest survival instincts – disgust. It prevented our ancestors from eating spoiled foods, but it does more than make us gag and screw up our noses; it also changes how we behave towards others. Just as lepers were exiled to colonies throughout the ages, and HIV+ people were shunned in more recent times, the threat of infection, be it legitimate or not, drives us to separate ourselves from those we judge as threats to our health. That might not come as much of a surprise to you; however, what it does to our moral and political beliefs is downright disturbing.

Experiments show that the mere suggestion of ‘infection’ made participants more conservative and conformist in their political views, changed their dating patterns, and made them more xenophobic and aggressive. This impact extends beyond the research lab. History is replete with examples of groups being stigmatised with disease labels; famously, the 1918 flu was commonly labelled ‘the Spanish flu’, and in turn, the Spanish called it ‘the French flu’. AIDS was originally called “gay-related immune deficiency”, while Nazi propaganda invoked imagery of rats to trigger disgust toward Jewish populations.

Source: Kramer, P., Bressan, P. Infection threat shapes our social instincts. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 75, 47 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-021-02975-9

This rise of xenophobic politics during pandemics is not confined to the history books; a real-world study of 31 countries showed that increased levels of parasites in societies predicted support for xenophobic policies and authoritarian governments. This should be cause for pause and contemplation. How has the pandemic affected our feelings towards ‘others’? Is the pandemic making us more insular, intolerant and aggressive?

How has the pandemic affected our feelings towards ‘others’?

Is the pandemic making us more insular, intolerant and aggressive?

Brains Don’t Let the Truth Get in the Way of a Good Story.

Traditional concepts of the mind described it functioning as a video camera, capturing information coming from our senses and turning it into a reasonably realistic movie in our heads. That idea no longer holds water. Instead, researchers have come to the unnerving realisation that our brain generates concepts first, then decides if they’re a ‘good enough’ match with reality. In the words of neuroscience researcher Dr Lisa Feldman Barrett,” your day-to-day experience is a carefully controlled hallucination”.

This allows us to anticipate and respond quickly to our environment, but it’s also prone to error. This is a salient point right now because it teaches us that ‘truth’ is not the number one priority of the brain. Any narrative that’s ‘good enough’ to reduce the anxiety of uncertainty and get us through the day will do. The less information we have to work with, the more our brain fills in the gaps, often leading to an illusory pattern perception, which it turns out, predicts supernatural and conspiratorial thinking. Compounding this problem is the fact that these false beliefs are written largely outside of our conscious awareness, yet we experience them consciously as unshakeable truths. From there, confirmation bias takes care of the rest, and the self-sealing loop of delusion is complete.

Pandemics create an abundance of anxiety, and so it’s no surprise that historical records reveal that conspiracy theories and pandemics run hand in hand. Pandemics are especially suited to triggering our darkest imaginations; to begin with, the attacker is invisible. Secondly, while in ages past we might have speculated about capricious gods and demons, today we have sciences so specialised and sophisticated that to all but a few experts, it’s as incomprehensible as magic. When presented with so much incomplete information, our imagination can’t help but fill the gaps. Making matters worse, the more anxious and depressed we are, the more negative those stories become. Thus, the chronic fear and uncertainty we’ve all felt since the pandemic began has driven many to create ever more elaborate explanations for the world around them.

Pandemics create an abundance of anxiety, and so it’s no surprise that historical records reveal that conspiracy theories and pandemics run hand in hand.

Desperate Times Cause Desperate Thinking

This brings us to the interaction between a lack of community belonging and the rise of conspiracy theories. The past decade has seen the exponential rise of social media; and alongside it, conspiracy narratives fed by misinformation, and disinformation. Now, it’s reaching a fever pitch and increasingly seen as a genuine existential threat to civilisation; clearly the social media companies have a lot to answer for, but so too do certain mainstream and alternative media networks.

Isolation erodes this sense of personal and social identity, creating a vacuum that marketers, politicians, and extremist groups are all too eager to exploit.

However, beyond the algorithms hijacking our amygdala, there’s a question around why some people are more susceptible to conspiracy theories than others.

Our social connections are fundamental in forming our sense of identity. Isolation erodes this sense of personal and social identity, creating a vacuum that marketers, politicians and extremist groups are all too eager to exploit.

Professor Stephan Lewandowsky and John Cook know a thing or two about what lures people into believing and sharing conspiracy theories; so much so they wrote a guidebook about it. They posit four key factors that increase someone’s likelihood of believing and sharing conspiracy theories.

- Feeling of powerlessness. When we feel threatened by the world, conspiracy theories give us a sense of control.

- Coping with threats. We struggle to accept that ‘big’ events can have mundane causes.

- Explaining unlikely events. We use conspiracy theories as a coping mechanism for uncertainty.

- Disputing mainstream politics. Groups use conspiracies to claim minority status and challenge dominant political groups.

Feeling alone makes us feel small and vulnerable and thus extra-susceptible to conspiracy theories as they offer the illusion of knowledge, safety, security, and self-esteem.

The imperative question then becomes; how can we inoculate people from fearful and fanciful thinking?

Feeling alone makes us feel small and vulnerable and thus extra-susceptible to conspiracy theories as they offer the illusion of knowledge, safety, security, and self-esteem.

The Path Out of Polarization

When it comes to changing someone’s beliefs, facts alone show limited efficacy. This is because our beliefs, especially our shared beliefs, are central to our sense of identity and belonging. In fact, when presented with evidence that threatens our beliefs or identity, we instinctively dismiss them. This was demonstrated in a large scale 2018 study exposing right-wing and left-wing Twitter followers to counterevidence on their respective political parties. Instead of depolarising the followers, they became more entrenched in their views. Echoing this finding, one of the most cited pieces of neuroscience research papers showed “challenges to political beliefs produced increased activity in the default mode network-a set of interconnected structures associated with self-representation and disengagement from the external world.“

This is not to say that presenting facts is a waste of time. Instead, it’s more nuanced. Salespeople, marketers or cult recruiters have known all along that the recipe for getting people across the line is simple; “first hook them with the heart, then go for the head”.

Dismissing people under the banner of “anti-vaxxer” repeats the same error of history, stigmatising and marginalising people with labels. This, in turn, creates an ‘us and them’ mentality, which drives further division and destroys any chance of connecting.

For those who are on the fence, high-quality facts presented in a respectful and heartfelt manner may be all they need. However, for those who are deeply wedded to their beliefs because they are bound up in their sense of identity and belonging, we need to find another route.

Lewandowsky and Cook also have advice in this area.

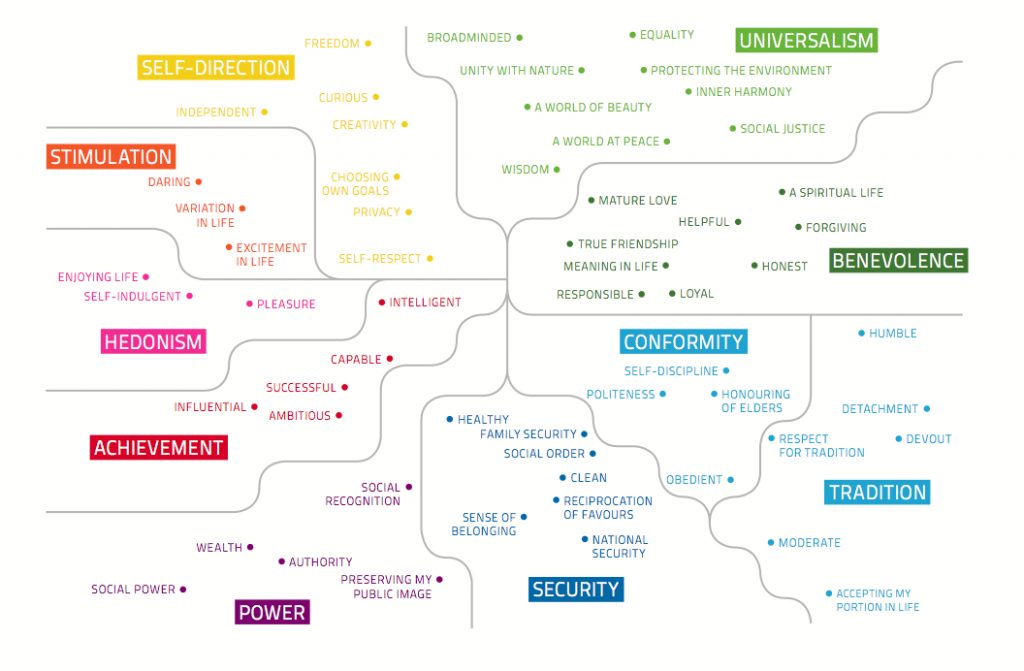

- Show empathy. Put yourself in their shoes, and try to understand what underlying factors are driving their thinking, e.g. uncertainty, anxiety, distrust of authority. Personally, I use social psychologist, Shalom Schwartz’s values map to help me tap into their core values.

- Avoid ridicule. Do not mock, denigrate, dismiss or disparage. Instead, lean in with compassion and curiosity.

- Trusted messengers. Who communicates the message is key. They need to be sufficiently trusted, and respected by the person receiving the message.

- Affirm critical thinking. Only once you have the previous three principles in place should you consider probing their logic – too soon and it’s likely to blow up in your face. Socratic questioning can be a good place to start, but it’s by no means the only way.

I would also add a fifth principle. Don’t stereotype. The reality is vaccine hesitancy is multifaceted. For some it is the result of falling for fake news; others however, have personal reasons such as traumatic medical experiences. For some, the alleged conspiracy isn’t so much to do with the vaccine, but rather they fear our freedoms will never be given back. Whatever the theory, to them, it’s important, and dismissing people under the banner of “anti-vaxxer” repeats the same error of history; stigmatising and marginalising people with labels. This, in turn, creates an ‘us and them’ mentality, which drives further division and destroys any chance of connecting.

Image Source: https://thepsychologist.bps.org.uk/volume-31/june-2018/ive-built-good-mousetrap-and-people-come-use-it

The points mentioned above are primarily suited for one-to-one conversations. There is, of course, a much larger question about what we need to do at a societal level. ‘Prebunking‘ is one option whereby the population is educated beforehand of likely forms of misinformation and manipulative tactics. There is also promise of Arg-tech, in which humans can debate with AI to clarify their thinking, however, given the suspicion many people have of AI, its popularity and effectiveness remain to be seen. Neither of these options however, deal with the question of what creates fertile ground for conspiracy thinking. For that, we need to return to the topic of community belonging.

Social researcher Hugh McKay AO has studied Australian society for almost half a century. In his 2018 book Australia Reimagined: Towards a more compassionate, less anxious society, he explored the ramifications of rising societal disconnection and gave a prescient warning of where we find ourselves today; “a society under this kind of stress is likely to display three clear symptoms:

- a heightened and unrealistic yearning for certainty, often expressed in the flight to the black-and-white simplicities of fundamentalism

- an obsession with security and control, expressed in a willingness to accept more rules and regulations, more surveillance, and more bars on our windows

- a retreat into a cocoon of self-absorption“

The path out of polarisation, requires a societal level reduction in anxiety, and that McKay argues, requires two key ingredients; greater compassion for one another and creating a sense of community belonging.

Fostering greater compassion

How we relate and communicate with one another, both public and private, matters. When we are quick to make assumptions, label, judge, and blame – we divide and diminish ourselves and others. Instead, we are better off listening to understand; aiming to connect, not coerce.

The medium of communication also matters; people are less empathetic when communicating over the internet compared to face-to-face. Unsurprisingly, this has been followed by the emergence of ‘cancel culture’, creating a chilling effect on civil discourse. In fear of being publicly doxxed and dunked on, we retreat back into our echo chambers, where we learn little and our vision of the world atrophies. So before you hit enter on your retort to the next raging facebook debate, ask yourself, would I say this to someone in person?

At a national level, politics and media (including mainstream, alternative, and social) foment fear and suspicion. This is not by accident, they know that fear and suspicion are reliable ways to hijack our attention, and attention is their currency. Since we’re wired in the womb to respond to these signals, it’s unlikely they will ever give this up; the only choice that remains for us then is to make a conscious effort to limit our exposure and reward those sources that rise above the rabble.

How to create community belonging?

As McKay puts it, “the state of our nation actually begins in our street”. Every time we make an effort to chat to a neighbour or smile at a passerby, we acknowledge their existence and repair the fabric of our society. These small gestures of humanity have a positive impact, but actions speak louder than words. Helping each other out with daily tasks, organising events together, and providing support in times of need, is what shifts us away from competition and towards cooperation.

Our community also extends beyond our street. There is an abundance of community groups and volunteering organisations in want of your helping hands. To help you deepen your community connections Allos Australia put together a calendar full of resources.

The situation we find ourselves in today is a systemic issue, which requires macro, meso, and micro-level interventions; however, for you and me, McKay’s reflection is one for us all.

“We are, each of us, organically linked to the whole; its problems are our problems; the pain of any is the pain of all. We cannot remain aloof from it unless we have found a way of hiding in a cocoon of self-absorbed individualism. Indeed, if we choose to remain aloof, in what sense can we call ourselves Australians?”

Mackay, H. (2018). Australia Reimagined: Towards a More Compassionate, Less Anxious Society. Australia: Pan Macmillan Australia.