A summer day turned into the scariest day of my life

Saturday 23rd December 2017 was a beautiful summer day in Melbourne. I was about to experience my first Christmas in summer, and my fiance had decided we would get ourselves some nice food from our favourite Italian supermarket. That morning he wanted to take the car, but I insisted we should cycle: I had been on a career break for a few months and had started to explore the city on my bike, so I was very excited to guide him around for the first time since I had moved to Australia 10 months earlier.

I was so happy cycling and excited for the day ahead. Suddenly, as I started crossing Lygon Street in Carlton, I heard an engine noise, turned my head to the right and saw a white car barreling towards me. The next thing I remember is lying on the road metres away from the pedestrian crossing, surrounded by people preventing me from getting up as all I wanted was to grab my bike and get on with my day. Then I realised what had happened and started sobbing, “We should have taken the car!”.

An ambulance arrived and took me to the hospital, where I spent 12 hours going through all sorts of checks. They wanted to keep me for the night under observation, but I wanted to leave – we had a plane to catch 15 hours later to get married on a beach in Samoa.

Strangely, I actually felt great at the time. Was I high on morphine and adrenaline, or was it my husband-to-be’s stupid jokes keeping me happy? I was laughing, chatting with the hospital staff, texting and calling my friends and family to tell them what had happened. I reassured them I was fine. Everyone was very supportive. Their initial anxiety gave way to relief when I told them the scans showed that all I had was some bad bruising.

From acute pain to chronic pain

The whiplash pain started on Christmas day. I didn’t sleep for days, but after our wedding day, the pain got better. My only symptom was a very swollen right knee and a limp. When we got back to Melbourne two weeks later, I saw my GP as soon as possible and was referred to a physiotherapist.

After six weeks, the acute pain had still not subsided in my lower back and left hip, and I still couldn’t lie down on my left side. The physiotherapist requested further scans. Surprisingly, they showed a fracture in my right knee and three fractures in my pelvis on the right side. I was confused; my pain had always been on the left side of my spine. I kept going to my physiotherapist, but the pain did not subside. I got mad at my husband for driving me places because simply sitting in the car was excruciating.

At the same time, people started telling me that my pain should have gotten better by now. It had been three months after my accident, then four, then five, but my chronic pain not only persisted, it became more severe. I kept asking my GP for help. I was given referral after referral to other doctors, who all explained that my chronic pain was because “my nervous system had become sensitised”. It was of little solace. My body was aching, I wanted to know what was going on, and instead, doctors wanted to put me on antidepressant medication.

Ten months later, I still struggled to leave my bed in the morning and started crying randomly throughout the day. Ironically, I really was depressed now. I looked for a new doctor, who told me “it’s all in your head”. I cried all the way home.

I looked for a new doctor, who told me “it’s all in your head”. I cried all the way home.

That was it, I thought; I was going crazy. No one was listening to me. I was in pain, but no one cared anymore.

Most of my friends and family were fed up hearing about my ongoing pain. On top of all the regular daily activities I could no longer do, I knew my husband was missing our hikes and bike rides, so I didn’t mention the pain and instead suffered in silence.

I was alone in my pain and getting more depressed and hopeless by the day. I begged my GP for help. When she said I could join a pain management program, I immediately said ‘Yes!’. I was willing to do anything that could free me.

The Pain Management Program

I started the pain management program at the end of November 2018. I thought the pain clinic would be full of doctors and clinical pain specialists, here to fix my pain.

Instead, a counsellor led me to a room where five people and a physiotherapist talked and sipped tea. For the first time since my accident, I was surrounded by other people living with chronic pain and a physiotherapist facilitating group discussions about pain and strategies to live with it.

If I had known this program would be a mix of support group, classroom-style teaching and exercise, I am not sure if I would have joined it. I was so focused on fixing my physical pain that I had no idea how much of it was linked to my mental state – I was even in denial of it.

“I was so focused on fixing my physical pain that I had no idea how much of it was linked to my mental state – I was even in denial of it.”

Of course, that first day did not reduce my persistent pain, but being able to talk about it with people who empathised with my story as well as hear others’ stories was eye-opening. Suddenly I was not alone anymore. I was not crazy. Without exaggeration, I can say it was one of the best days of my life. The program took place two days a week over six weeks, and it was life-changing for me.

Reading this, you may think, “come on, you must have known that millions of people around the world live with chronic pain”. Of course, I did. But this was the difference between reading academic statistics online versus sharing real experiences, face-to-face, with people who understood me. While none of us were doctors, life had made us all pain specialists. Without the pain management program, I wouldn’t have found that connection.

This is a small yet massive difference. It taught me the power of surrounding ourselves with people who relate to what we’re going through.

How community belonging reduces persistent pain

One of the first things I learned in the pain management program is that anyone living with chronic pain experiences a mix of three components – I’m citing the physio’s language here:

- Hardware (body): injury, “issues in the tissues”

- Software (nervous system): central sensitisation

- Wetware (chemicals): “the drug cabinet in the brain”

This last point is about the hormones our body produces and are involved in all sorts of situations in our lives. The adrenaline my body released during my accident enabled my ‘fight or flight’ response and stopped me from feeling pain as I lay on the road after the crash.

But there are other hormones that our which influence how we feel pain. One example of this is oxytocin, otherwise known as the “cuddle hormone“. As more and more studies show, this has the power to reduce physical pain.

It looks like this is not just about physical pain but emotional pain too. Mechanisms of the brain are not yet entirely understood, but a study published in early 2021 found that couples holding hands while recollecting painful memories experienced lower emotional pain over the longer term.

While the accident had triggered my fight-or-flight response, the pain management community has triggered my tend-and-befriend response, releasing powerful endogenous opioids into my system. My new friends were my morphine.

Couples holding hands while recollecting painful memories experienced lower emotional pain over the long-term

Have you ever appreciated the power of a hug when grieving or heartbroken? That’s oxytocin at work.

From a counselling perspective, the positive influence of social interactions on pain, both physical and emotional, makes perfect sense. All widely recognised developmental theories recognise that nature and nurture are interlinked in how we develop behaviours and patterns of thoughts. A significant part of nurture is about the people in our lives, and it’s not just limited to our childhood. Knowing we are loved and belong increases our pain tolerance and improves healing.

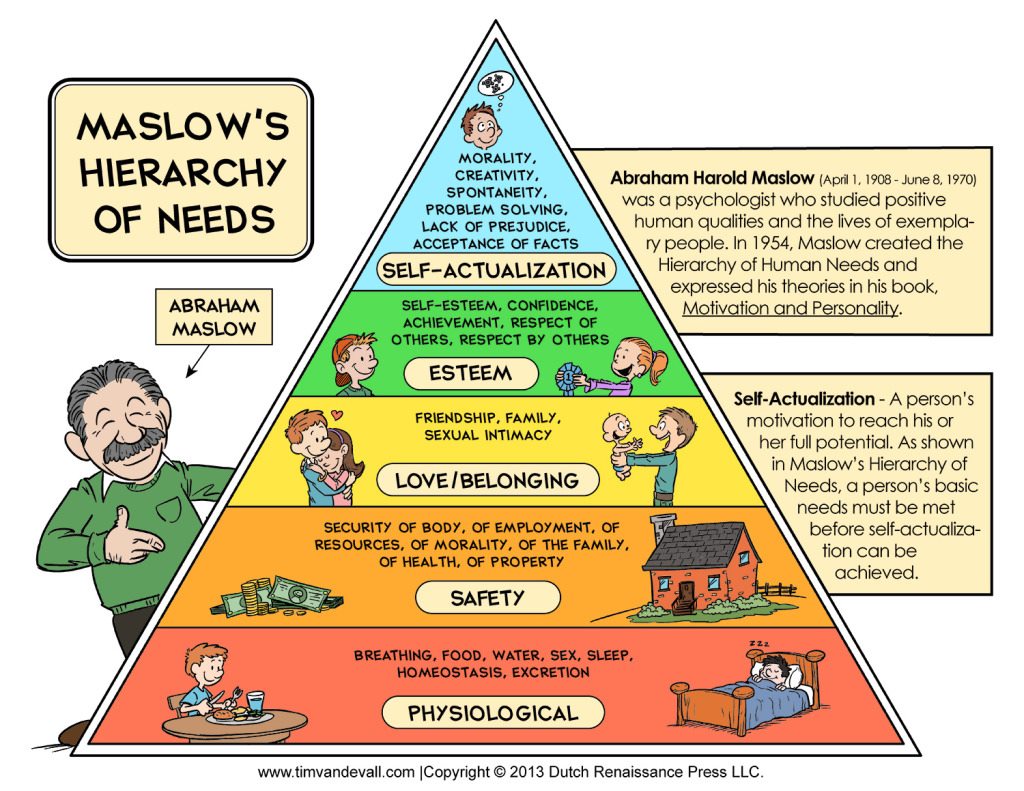

Looking at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, belonging and love come right after basic physiological and safety needs:

This makes it easy to understand why being surrounded by other people living with chronic pain made such a difference to my experience and helped me not only cope with the persistent pain but also lift me out of the depression I was in.

This is not just a lesson about recovering from traffic accidents. It’s about how we live our lives. Think about how good it feels to join a book club if you love reading or an entrepreneurs meet-up if you have been thinking about starting your own business. There is huge power in interacting with people who share the same passions and challenges as us.

“being surrounded by other people living with chronic pain made such a difference to my experience and helped me not only cope with the persistent pain but also lift me out of the depression I was in.”

These don’t have to be physical meetings either. Online forums or social media groups provide a place to connect and ask questions about things your close circle might not be interested in or open to.

My tip for strengthening your village

The following tip is again something I learnt from the pain management program, but I absolutely love it because it applies to anyone, whether they live with chronic pain or not.

It is called DIM-SIM – easy to remember, right?

The aim is to evaluate what, in your life, brings “Danger in Me, and Safety in Me”.

Here’s an exercise: evaluate DIM-SIMs for all areas in your life:

- people

- places

- things we do

- things we sense

- things we believe

- things we say

- things happening in our bodies

For example, think of who brings up “danger” or “safety” feelings in your life.

If you reflect on your life throughout the pandemic, who has been a pillar for your emotional health? You may be surprised to find that people you were not that close to before the pandemic have shown themselves to be sources of strength and support.

Some people we have talked to lately shared that they’ve been touched by the care their neighbours have shown during lockdown. Remember those videos of people playing music on their balconies during lockdown? Seems like this is still a thing in some parts of Australia! Someone else mentioned that they had joined a wellness centre who created a group conversation which lifted their participants’ spirits. These are all examples of how we can build our ‘village’.

It is also good to remember that our need for connection, and ability to connect, vary with phases in our lives. For some, having children means they have no time to spend with ‘their village’. So when you do your DIM-SIM, take into account the people you may not talk to regularly but whom you know you can count on anytime. Give them a call.

Final Thoughts and Gratitude

Nearly four years after my accident, I finally feel that my life is back on track. I still have chronic pain; actually, I woke up with a terrible headache this morning. But I have learnt to live with the pain.

Things have not been perfect, and it took a few years before I found the right physio and psychologist to help me not only live with my pain, but thrive in spite of it. I am back to cycling too, something I had given up on. As of August this year, I no longer see my psychologist as we both agreed that I am now able to cope on my own.

“it took a few years before I found the right physio and psychologist to help me not only live with my pain, but thrive in spite of it”

I am very thankful for the community that has helped me along this journey. This includes the people closest to me and the Australian health system, and the Transport Accident Commission, which is still supporting me on the last steps of my recovery. My GP never gave up trying to find the best support for me. I had access to mental health professionals, whether through the TAC or Mental Health Care Plans.

And if I can make a comparison with my country of birth, France, I am so impressed by how mental health is treated here.

Can you believe that in France, counsellors don’t exist – there is actually no word for “counsellor” in French – and that psychiatrists are the only health professionals that are covered by the French national health system? This means people have to pay themselves if they want to see a psychologist or other health professionals in the mental health space.

Like Australia, France’s mental health system is overwhelmed, but I believe that we should be thankful for what we have.

And please, if you read this and are not coping on your own, make use of the health service. You’re worth it.